MAURICE RAVEL (1875 – 1937): L’enfant et les sortilèges and Ma mère l’Oye—Hélène Hébrard (L’enfant), Delphine Galou (Maman, La libellule, La tasse chinoise), Julie Pasturaud (La bergère Louis XV, La chatte, L’écureuil, Un pâtre), Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (La théière, Le petit vieillard, La rainette), Marc Barrard (L’horloge comtoise, Le chat), Nicolas Courjal (Le fauteuil, Un arbre), Ingrid Perruche (Le chauve-souris, La chouette, Une pastourelle), Annick Massis (Le feu, La princesse, Le rossignol); Chœur Britten, Jeune Chœur symphonique, Maîtrise de l’Opéra National de Lyon; Orchestre National de Lyon; Leonard Slatkin, conductor [Recorded in Auditorium Maurice Ravel, Lyon, France, in September 2011 (Ma mère l’Oye) and 22 – 26 January 2013 (L’enfant et les sortilèges); NAXOS 8.660336; 1 CD, 71:52; Available from ClassicsOnlineHD, Amazon (USA), jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

MAURICE RAVEL (1875 – 1937): L’enfant et les sortilèges and Ma mère l’Oye—Hélène Hébrard (L’enfant), Delphine Galou (Maman, La libellule, La tasse chinoise), Julie Pasturaud (La bergère Louis XV, La chatte, L’écureuil, Un pâtre), Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (La théière, Le petit vieillard, La rainette), Marc Barrard (L’horloge comtoise, Le chat), Nicolas Courjal (Le fauteuil, Un arbre), Ingrid Perruche (Le chauve-souris, La chouette, Une pastourelle), Annick Massis (Le feu, La princesse, Le rossignol); Chœur Britten, Jeune Chœur symphonique, Maîtrise de l’Opéra National de Lyon; Orchestre National de Lyon; Leonard Slatkin, conductor [Recorded in Auditorium Maurice Ravel, Lyon, France, in September 2011 (Ma mère l’Oye) and 22 – 26 January 2013 (L’enfant et les sortilèges); NAXOS 8.660336; 1 CD, 71:52; Available from ClassicsOnlineHD, Amazon (USA), jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

One of the most popular pastimes among opera lovers is lamenting the extinction of the nationalistic schools of singing that in near-mythic previous generations divided opera companies' rosters into adherents of the particular styles of French, German, and Italian opera. This new NAXOS recording of Maurice Ravel's exquisite masterpiece-in-miniature L'enfant et les sortilèges reveals in every second of its forty-five minutes that the death knell for the storied French school of singing was rung prematurely. Here, some of today's best French-speaking singers proclaim to the listener that, as Mark Twain might have said, the rumors of the demise of distinctive, distinguished French singing have been greatly exaggerated.

It is indicative of her esteem not only for the composer's work but also for her own that, when the Opéra de Paris proposed to the celebrated French writer Colette that she write the text for a fanciful work for the stage, she was enthusiastic about no collaborator but Ravel. Her libretto for the piece that became L'enfant et les sortilèges took shape in only eight days—an ironic rapidity considering the snail's pace at which the notoriously unhurried Ravel, distracted by his service in the Great War and his mother's death, composed the score. Colette was among the first listeners to realize that Ravel's music was worth the wait: few writers in the history of opera have witnessed their words as lovingly integrated with music as Colette's are with Ravel's music in L'enfant et les sortilèges. Effective recreation of that integration of words and music must be the core of a performance of L'enfant et les sortilèges if it is to be successful, and the performance recorded by NAXOS—a souvenir of live performances, discreet coughs suggest, though this is not specified in the liner notes—balances verbal and musical values on equal footing.

Coupled with a nuanced, surprisingly touching performance of Ravel's 1911 fully-orchestrated ballet suite Ma mère l’Oye, the Orchestre National de Lyon and the ensemble's Music Director, American conductor Leonard Slatkin, collaborate in a reading of L'enfant et les sortilèges that journeys into the dark corners of music and text without getting lost in them. Slatkin's relationship with opera has been tempestuous, particularly in the wake of his widely-publicized withdrawal from performances of Verdi's La traviata at the Metropolitan Opera in 2010, when he alleged, in response to her suggestions that he was inept and unprepared, that his Violetta was insufferably unprofessional. [The often ridiculous politicking of opera is evident in the fact that Slatkin has not returned to the MET since 2010, whereas the soprano in question has appeared numerous times in the subsequent five years, on increasingly precarious form.] Conducting Ravel's and Verdi's scores are very different tasks, and if Slatkin does not achieve the authority and authenticity in L'enfant et les sortilèges that Ernest Bour and Ernest Ansermet exhibited in their recordings of the opera he manages to come very near to their high-water mark. The acoutics on this disc are not as spacious or well-defined as those on many NAXOS recordings, but the countless witticisms of Ravel's orchestrations are never obscured. On the whole, Slatkin's approach to the score is admirable, his tempi suitable for both the music and the personnel performing it. Under his direction, the Lyon musicians play with technical and sentimental virtuosity, unafraid of conveying a degree of saccharine eye-dabbing when Maman's naughty child unexpectedly binds the foot of the squirrel he injured. This is all to the good, for the moment is, somehow, incredibly poignant. Colette and Ravel clearly thought so: Slatkin and Company ensure that the listener thinks—and feels—so, too.

The ladies and gentlemen of all ages of the Chœur Britten, Jeune Chœur symphonique, and Maîtrise de l’Opéra National de Lyon bring their music to life with involvement that makes portraying inanimate objects and woodland creatures sound like the greatest fun in the world. The elegy for the casualties of the child’s assault on the Arcadian wallpaper, ‘Adieu, Pastourelles,’ is sung with an endearing element of sincerity. The various noises of the sylvan environment into which the child is plunged are produced with obvious relish: every hoot, howl, chirp, and croak is delivered with the same conviction with which the singers uniformly enunciate text. The menace that erupts from the choristers’ utterance of ‘Ah! C’est l’enfant au couteau!’ is genuinely frightening, and the contrast with the startled disbelief of their ‘Il a pansé la plaie’ when the denizens of the forest realize that the child has bandaged the squirrel’s wounded paw could hardly be more meaningful. The grand chorus that ends the opera, ‘Il est bon, l’enfant, il est sage,’ virtually a Baroque motet in which the animals find their own voices in order to call out for the child’s mother, is sung handsomely, but here, too, it is the spirit of the singing that is most impressive.

As entrancingly as her voice flickers in the coloratura and top Cs and D of La feu's ‘Arrière! Je réchauffe les bons,’ soprano Annick Massis shines even more brightly as La princesse, her singing of ‘Ah! Oui, c’est Elle, ta Princesse enchantée’ elucidating the impetus for the child's despair when he learns that, owing to his destructive misbehavior, there is no resolution to the princess's story. Massis is at her best as Le rossignol, warbling through the avian trills and top Ds with complete confidence. Simply put, Massis is one of the world’s most talented singers, one with acclaimed performances in the most important opera houses to her credit, but she inexplicably is not as familiar to American audiences and listeners as she deserves to be. For those who do not know her work, this recording will be a wonderful introduction. With refined, engaging accounts of Une pastourelle's ‘Pâtre de ci, Pastourelle de là’ and La chauve-souris's ‘Rends-la moi,’ soprano Ingrid Perruche nearly equals Massis's performance, differentiating her characterizations without deviating from her innate artistic integrity and loveliness of tone. Nicolas Courjal, an exceptionally gifted young bass, impresses with his imaginative singing of Le fauteuil's ‘Votre serviteur humble, Bergère’ and targets the heart with the skill of an expert marksman in his sonorous but sensitive phrasing of Un arbre's anguished 'Ah! Ma blessure...Ma blessure.'

As L’horloge comtoise, the grandfather clock deprived of its pendulum by the child's roughhousing, baritone Marc Barrard intones 'Ding, ding, ding, ding' with near-mechanical precision, but he gives one of the recording's most brilliantly uninhibited performances as Le chat in the riotous ‘Duo miaulé,’ an homage to Wagner's chromatically adventurous writing for Tristan and Isolde that only a pair of agitated felines could bring off. Tenor Jean-Paul Fouchécourt is a marvel of a singer in the tradition of Michel Sénéchal whose performances radiate very French sensibilities. That he chants as much as he sings in this performance is more to do with the nature of his music, in which Ravel gives him absurd writing rocketing to E♭5 and F5 in falsetto, than with the condition of the voice, which remains in fine fettle. Fouchécourt purrs La théière's ‘How’s your mug?’ with the snobbishness of a very proper English lord before whirling uproariously through the famous Foxtrot. He is even more in his element as Le petit viellard, spouting Old Man Arithmetic's drolleries in ‘Deux robinets coulent dans un réservoir!’ as though they were choicest lines from Shakespeare. Both gentlemen are complemented by the alert, well-honed singing of mezzo-soprano Julie Pasturaud, a Bergère Louis XV whose 'Votre servante, Fauteuil’ is noticed and a Pâtre whose 'L’enfant méchant a déchiré’ has both substance and subtlety. She matches Barrard meow for sultry meow as La chatte in ‘Duo miaulé.’ As L'écureuil, the much-abused squirrel, Pasturaud excels at infusing the little creature with humanity, articulating ‘Sauve-toi, sotte! Et la cage? La cage?’ with grace that highlights her tormenter’s inherent savagery.

Heard most frequently in Baroque repertory, contralto Delphine Galou creates a Maman whose profoundly expressive ‘Bébé a été sage?’ exudes maternal affection despite the exasperation caused by a disobedient child. When this mother sings of the hurt that she suffers because of her son’s recalcitrance, her pain stokes the listener’s sympathy. Galou metamorphoses into La tasse chinoise as if by the enchantment evoked in the opera’s title. She sings the mock-Chinese jibberish in ‘Keng-ça-fou, mah-jong’ as though she were quoting Confucius. Then, she gives the despondent La libellule a soul with her aggrieved voicing of ‘Où es tu, je te cherche.’ Mezzo-soprano Hélène Hébrard depicts an Enfant who is petulant and frustratingly puerile at the start but ultimately atypically poetic. The ennui of her ‘J’ai pas envie de faire ma page!’ and ‘Ça m’est égal!’ is unmistakable, but deeper emotions intrude in ‘Oh! Ma belle tasse chinoise!’ These emotions escalate in Hébrard’s impassioned exchange with the Princesse, ‘Ah! C’est elle! C’est elle!’ She etches the essence of ‘Toi, le cœur de la rose’ into the listener’s memory, and her exclamation of ‘Oh! Ma tête!’ is wrenching. The relief that Hébrard conveys with ‘Ah! Quelle joie de te retrouver, Jardin!’ is sweetly comforting, and her final ‘Maman’ breaks both the drama’s and the opera’s spells. Hébrard credibly portrays a child without endeavoring to sound conventionally childish, but this Enfant emerges from his ensorcelled forest with remarkable maturity.

NAXOS releases often illuminate aspects of scores that other recordings leave in the shadows, and this recording of Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye and L’enfant et les sortilèges exposes these chameleonic works to the shimmering Lyonnais sun. Like ragtime and jazz, far more musicians perform the music of Maurice Ravel than actually understand it. This disc provides a rare encounter with two of Ravel’s most beautiful pieces that is guided by the efforts of musicians who both grasp the composer’s singular idiom and truly love the music. This is a L’enfant et les sortilèges to reawaken the incorrigible but good-hearted child in every listener—and the dormant love for true French opera that has longed for signs of life.

![IN PERFORMANCE: Giacomo Puccini's MADAMA BUTTERFLY at North Carolina Opera, October/November 2015 [Illustration of Cio-Cio San's rejection by her relations by Leopoldo Metlicovitz (1868 - 1944), © by Casa Ricordi] IN PERFORMANCE: Giacomo Puccini's MADAMA BUTTERFLY at North Carolina Opera, October/November 2015 [Illustration of Cio-Cio San's rejection by her relations by Leopoldo Metlicovitz (1868 - 1944), © by Casa Ricordi]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-sEufNWy5L10/VjUXg6LrqZI/AAAAAAAAFOc/aT1TaVD5y64/Puccini_Madama-Butterfly_Illustratio%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Madama Butterfly—

GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Madama Butterfly—![IN PERFORMANCE: Giacomo Puccini's MADAMA BUTTERFLY at North Carolina Opera, October/November 2015 [Illustration of Sharpless reading Pinkerton's letter by Leopoldo Metlicovitz (1868 - 1944), © by Casa Ricordi] IN PERFORMANCE: Giacomo Puccini's MADAMA BUTTERFLY at North Carolina Opera, October/November 2015 [Illustration of Sharpless reading Pinkerton's letter by Leopoldo Metlicovitz (1868 - 1944), © by Casa Ricordi]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-oyYkY5GDbMk/VjUXhWzz6pI/AAAAAAAAFOg/yvoZMhUorOg/Puccini_Madama-Butterfly_Illustration-by-Leopoldo-Metlicovitz_Ricordi_Che-tua-madre%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Qui sedete, legger con me volete questa lettera: Sharpless reads Pinkerton’s letter in Act Two of Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly [Illustration by Leopoldo Metlicovitz, © by Casa Ricordi]

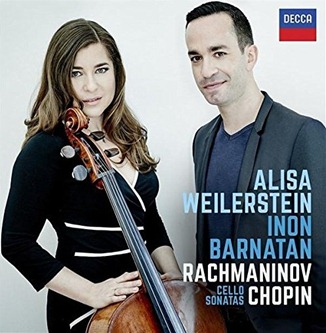

Qui sedete, legger con me volete questa lettera: Sharpless reads Pinkerton’s letter in Act Two of Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly [Illustration by Leopoldo Metlicovitz, © by Casa Ricordi] FRÉDÉRIC FRANÇOIS CHOPIN (1810 – 1849): Sonata for cello and piano, Op. 65; Étude, Op. 25, No. 7 (arranged by Auguste Franchomme); Introduction et Polonaise brillante for piano and cello, Op. 3 and SERGEY RACHMANINOV (1873 – 1943): Sonata for cello and piano, Op. 19; Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14—

FRÉDÉRIC FRANÇOIS CHOPIN (1810 – 1849): Sonata for cello and piano, Op. 65; Étude, Op. 25, No. 7 (arranged by Auguste Franchomme); Introduction et Polonaise brillante for piano and cello, Op. 3 and SERGEY RACHMANINOV (1873 – 1943): Sonata for cello and piano, Op. 19; Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14— RICHARD WAGNER (1813 – 1883): Das Rheingold—

RICHARD WAGNER (1813 – 1883): Das Rheingold—![ARTIST PROFILE: Prince of the Piano - Italian pianist LUDOVICO TRONCANETTI [Photo © by the artist; used with permission] ARTIST PROFILE: Prince of the Piano - Italian pianist LUDOVICO TRONCANETTI [Photo © by the artist; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-RLcdRlnHYdI/VkFifH3Za-I/AAAAAAAAFQo/qoWZ24mV48c/Ludovico_Trocanetti_Piano_EDIT17.jpg?imgmax=800) Principe del pianoforte: Italian pianist Ludovico Troncanetti [Photo © by the artist; used with permission]

Principe del pianoforte: Italian pianist Ludovico Troncanetti [Photo © by the artist; used with permission]![ARTIST PROFILE - Prince of the Piano: Italian pianist LUDOVICO TRONCANETTI in performance [Photo © by the artist; used with permission] ARTIST PROFILE - Prince of the Piano: Italian pianist LUDOVICO TRONCANETTI in performance [Photo © by the artist; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-icD_CObhn4I/VkFift7H-AI/AAAAAAAAFQs/ivLp0y2RGK4/Ludovico_Trocanetti_In-Performance_EDIT%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) In performance: Italian pianist Ludovico Troncanetti in his natural habitat [Photo © by the artist; used with permission

In performance: Italian pianist Ludovico Troncanetti in his natural habitat [Photo © by the artist; used with permission![ARTS IN ACTION: Washington Concert Opera performs Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE on 22 November 2015 [Graphic © by Washington Concert Opera] ARTS IN ACTION: Washington Concert Opera performs Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE on 22 November 2015 [Graphic © by Washington Concert Opera]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-X5GnRLsIowE/VkN-9_YSNBI/AAAAAAAAFRE/dOktRKK1FGI/Semiramide_DC-Concert-Opera_Graphic%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![ARTS IN ACTION: Soprano JESSICA PRATT, Semiramide in Washington Concert Opera's 22 November performance of SEMIRAMIDE, as Amira in Gioachino Rossini's CIRO IN BABILONIA at Pesaro's Rossini Festival, 2012 [Photo by Eugenio Pini, © by Rossini Festival, Pesaro; used with permission] ARTS IN ACTION: Soprano JESSICA PRATT, Semiramide in Washington Concert Opera's 22 November performance of SEMIRAMIDE, as Amira in Gioachino Rossini's CIRO IN BABILONIA at Pesaro's Rossini Festival, 2012 [Photo by Eugenio Pini, © by Rossini Festival, Pesaro; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-zC47zapWteY/VkN_BJKejcI/AAAAAAAAFRU/EofHsA034-A/CiroinBabiloniaPesaroEugenioPini_thumb%25255B2%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Rossinian cousins: Soprano Jessica Pratt, Washington Concert Opera’s Semiramide, as Amira in Gioachino Rossini’s Ciro in Babilonia at Pesaro’s Rossini Festival, 2012 [Photo by Eugenio Pini, © by Rossini Festival, Pesaro; used with permission]

Rossinian cousins: Soprano Jessica Pratt, Washington Concert Opera’s Semiramide, as Amira in Gioachino Rossini’s Ciro in Babilonia at Pesaro’s Rossini Festival, 2012 [Photo by Eugenio Pini, © by Rossini Festival, Pesaro; used with permission]![ARTS IN ACTION: Mezzo-soprano VIVICA GENAUX, Arsace in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Michel Juvet; used with permission] ARTS IN ACTION: Mezzo-soprano VIVICA GENAUX, Arsace in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Michel Juvet; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-o1TMEdqTsn8/VkN_B2TYn-I/AAAAAAAAFRc/yegG4umiIno/IMG_8654-1c_pp-3%252520copie%252520sign%2525C3%2525A9-1%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Ardent Arsace: Mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux, Arsace in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Michel Juvet; used with permission]

Ardent Arsace: Mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux, Arsace in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Michel Juvet; used with permission]![ARTS IN ACTION: Tenor TAYLOR STAYTON, Idreno in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Amy Allen; used with permission] ARTS IN ACTION: Tenor TAYLOR STAYTON, Idreno in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Amy Allen; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-K1sz5osYemI/VkN_CJyUDkI/AAAAAAAAFRg/5wBx4evzsKI/Taylor-Stayton_Amy-Allen%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Idiomatic Idreno: Tenor Taylor Stayton, Idreno in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Amy Allen; used with permission]

Idiomatic Idreno: Tenor Taylor Stayton, Idreno in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide on 22 November 2015 [Photo © by Amy Allen; used with permission]

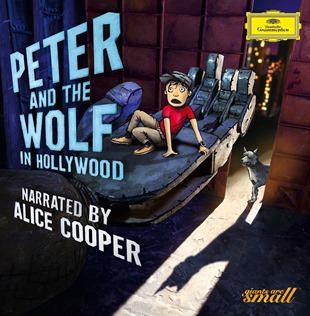

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 – 1953): Peter and the Wolf, Opus 67, plus music by Paul Dukas, Sir Edward Elgar, Edvard Grieg, Gustav Mahler, Modest Mussorgsky, Giacomo Puccini, Erik Satie, Robert Schumann, Bedřich Smetana, Richard Wagner, and Alexander von Zemlinsky—

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 – 1953): Peter and the Wolf, Opus 67, plus music by Paul Dukas, Sir Edward Elgar, Edvard Grieg, Gustav Mahler, Modest Mussorgsky, Giacomo Puccini, Erik Satie, Robert Schumann, Bedřich Smetana, Richard Wagner, and Alexander von Zemlinsky— CHARLES-FRANÇOIS GOUNOD (1818 – 1893): La colombe—

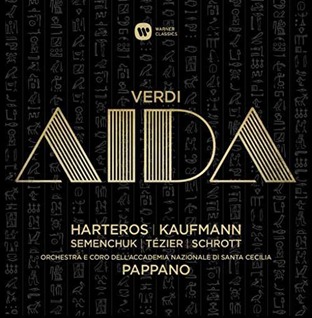

CHARLES-FRANÇOIS GOUNOD (1818 – 1893): La colombe— GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Aida—

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Aida—![IN PERFORMANCE: The cast of Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] IN PERFORMANCE: The cast of Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-Wyqd7gxV8Vs/VlPawZ6k8hI/AAAAAAAAFT8/pg-aZpGOYYE/taylor-stayton-vivica-genaux-jessica-pratt-maestro-antony-walker-wayne-tigges-evan-hughes_22616563834_o%25255B11%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868): Semiramide—

GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868): Semiramide—![IN PERFORMANCE: Bass WEÍ WU as L'ombra di Nino, bass-baritone WAYNE TIGGES as Assur, Maestro ANTONY WALKER, and the WCO Chorus and Orchestra in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] IN PERFORMANCE: Bass WEÍ WU as L'ombra di Nino, bass-baritone WAYNE TIGGES as Assur, Maestro ANTONY WALKER, and the WCO Chorus and Orchestra in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-etRfjn2kayg/VlPawxM1TcI/AAAAAAAAFUE/jiwo5P7B6eM/we-wu-with-maestro-antony-walker-wco-orchestra-and-chorus_22617894793_o%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) L’ombra e l’assassino: Bass Weí Wu as L’ombra di Nino (left, foreground), bass-baritone Wayne Tigges as Assur (center, on stage), Maestro Antony Walker, and the WCO Chorus and Orchestra in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]

L’ombra e l’assassino: Bass Weí Wu as L’ombra di Nino (left, foreground), bass-baritone Wayne Tigges as Assur (center, on stage), Maestro Antony Walker, and the WCO Chorus and Orchestra in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]![IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor TAYLOR STAYTON as Idreno in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor TAYLOR STAYTON as Idreno in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-8IwX4LFVC3E/VlPaxSEngvI/AAAAAAAAFUM/hFEWRqbQ50g/taylor-stayton_22850848317_o%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Il re di Rossini: Tenor Taylor Stayton as Idreno in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]

Il re di Rossini: Tenor Taylor Stayton as Idreno in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] L'uomo più piuttosto della festa: Mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux as Arsace in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]

L'uomo più piuttosto della festa: Mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux as Arsace in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]![IN PERFORMANCE: Mezzo-soprano VIVICA GENAUX as Arsace and soprano JESSICA PRATT in the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] IN PERFORMANCE: Mezzo-soprano VIVICA GENAUX as Arsace and soprano JESSICA PRATT in the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-OHmm2HfeX5c/VlPay_ZUphI/AAAAAAAAFUc/RYCoG1TLq8Y/vivica-genaux-jessica-pratt_22617891493_o%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Figlio e madre: Mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux as Arsace (left) and soprano Jessica Pratt (right) in the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]

Figlio e madre: Mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux as Arsace (left) and soprano Jessica Pratt (right) in the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]![IN PERFORMANCE: Maestro ANTONY WALKER, WCO's Artistic Director, during Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] IN PERFORMANCE: Maestro ANTONY WALKER, WCO's Artistic Director, during Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's SEMIRAMIDE, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-cf9TQ-mA038/VlPaze3KAeI/AAAAAAAAFUk/aGAmTV5ILCE/wco_donlassell-1140_16693051941_o%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Il Maestro: WCO Artistic Director and Conductor Antony Walker during Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera]

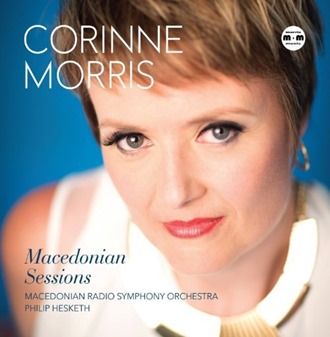

Il Maestro: WCO Artistic Director and Conductor Antony Walker during Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide, 22 November 2015 [Photo by Don Lassell, © by Washington Concert Opera] WOLDEMAR BARGIEL (1828 – 1897), MAX BRUCH (1838 – 1920), MANUEL DE FALLA (1876 – 1946), GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924), JULES MASSENET (1842 – 1912), CORINNE MORRIS, ASTOR PIAZZOLLA (born 1921), CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835 – 1921), PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840 – 1893), and JOHN WILLIAMS (born 1932): Macedonian Sessions—

WOLDEMAR BARGIEL (1828 – 1897), MAX BRUCH (1838 – 1920), MANUEL DE FALLA (1876 – 1946), GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924), JULES MASSENET (1842 – 1912), CORINNE MORRIS, ASTOR PIAZZOLLA (born 1921), CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835 – 1921), PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840 – 1893), and JOHN WILLIAMS (born 1932): Macedonian Sessions—

GIULIO CACCINI (1551 – 1618), FRANCESCO CAVALLI (1602 – 1676), JOAN AMBROSIO DALZA (1508 – ?), ANDREA FALCONIERI (1585 – 1656), GIROLAMO FRESCOBALDI (1583 – 1643), CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI (1567 – 1643), DIEGO ORTIZ (1510 – 1570), GASPAR SANZ (1640 – 1710), BARBARA STROZZI (1619 – 1677): Momenti d’amore—

GIULIO CACCINI (1551 – 1618), FRANCESCO CAVALLI (1602 – 1676), JOAN AMBROSIO DALZA (1508 – ?), ANDREA FALCONIERI (1585 – 1656), GIROLAMO FRESCOBALDI (1583 – 1643), CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI (1567 – 1643), DIEGO ORTIZ (1510 – 1570), GASPAR SANZ (1640 – 1710), BARBARA STROZZI (1619 – 1677): Momenti d’amore— [1] GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924): Ballade in F sharp major for Piano Solo, Opus 19 and MAURICE RAVEL (1875 – 1937): Piano Concerto in G major and Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major—

[1] GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924): Ballade in F sharp major for Piano Solo, Opus 19 and MAURICE RAVEL (1875 – 1937): Piano Concerto in G major and Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major—

![IN PERFORMANCE: Internationally-acclaimed pianist VALENTINA LISITSA [Photo by Gilbert François, © by DECCA / Universal Music Group] IN PERFORMANCE: Internationally-acclaimed pianist VALENTINA LISITSA [Photo by Gilbert François, © by DECCA / Universal Music Group]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-PZTgVOCbl7I/VmobflTzlrI/AAAAAAAAFY4/kWmqShGGj90/s320/Valentina-Lisitsa_Gilbert-Francois.jpg) ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH SCRIABIN (1872 – 1915): Préludes, Op. 11, Nos. 2, 4, 5, 10, 14 – 16, 20; Prélude, Op. 22, No. 1; Prélude, Op. 27, No. 1; Prélude, Op. 35, No. 2; Poème, Op. 41; Danse, Op. 73, No. 2 Flammes sombres; Polonaise, Op. 21; Poème tragique, Op. 34; and Poème satanique, Op. 36 and FRÉDÉRIC FRANÇOIS CHOPIN (1810 – 1849): Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 31 and 24 Études for Piano, Opp. 10 and 25–

ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH SCRIABIN (1872 – 1915): Préludes, Op. 11, Nos. 2, 4, 5, 10, 14 – 16, 20; Prélude, Op. 22, No. 1; Prélude, Op. 27, No. 1; Prélude, Op. 35, No. 2; Poème, Op. 41; Danse, Op. 73, No. 2 Flammes sombres; Polonaise, Op. 21; Poème tragique, Op. 34; and Poème satanique, Op. 36 and FRÉDÉRIC FRANÇOIS CHOPIN (1810 – 1849): Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 31 and 24 Études for Piano, Opp. 10 and 25– ![IN PERFORMANCE: Internationally-acclaimed pianist VALENTINA LISITSA [Photo by Gilbert François, © by DECCA / Universal Music Group] IN PERFORMANCE: Internationally-acclaimed pianist VALENTINA LISITSA [Photo by Gilbert François, © by DECCA / Universal Music Group]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-rFt3kc8jvZw/Vmoa_vdrIfI/AAAAAAAAFYw/AO-uM8GHVuo/s320/Valentina-Lisitsa-at-piano_Gilbert-Francois_DECCA.jpg) Artist in Action: Internationally-acclaimed pianist Valentina Lisitsa, recitalist in Duke Performances Piano Recital series at Baldwin Auditorium on the campus of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, 11 December 2015 [Photo by Gilbert François, © by DECCA / Universal Music Group]

Artist in Action: Internationally-acclaimed pianist Valentina Lisitsa, recitalist in Duke Performances Piano Recital series at Baldwin Auditorium on the campus of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, 11 December 2015 [Photo by Gilbert François, © by DECCA / Universal Music Group] CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK (1714 – 1787): Iphigénie en Tauride—

CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK (1714 – 1787): Iphigénie en Tauride— GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL (1685 – 1759): Messiah, HWV 56—

GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL (1685 – 1759): Messiah, HWV 56—

[1] AMILCARE PONCHIELLI (1834 – 1886): La Gioconda—Lucille Udovich (La Gioconda), Flaviano Labò (Enzo Grimaldo), Mignon Dunn (Laura Adorno), Aldo Protti (Barnaba), Norman Scott (Alvise Badoero), Luisa Bartoletti (La Cieca), Tulio Gagliardo (Zuàne), Italo Pasini (Isèpo), Guerrino Boschetti (Un cantore); Coro y Orquesta Estable del Teatro Colón; Carlo Felice Cillario, conductor [Recorded ‘live’ in the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 28 July 1970; Walhall Eternity Series WLCD 0337; 3 CDs, 200:28 (including Act One from a 1958 performance of Madama Butterfly); Available from

[1] AMILCARE PONCHIELLI (1834 – 1886): La Gioconda—Lucille Udovich (La Gioconda), Flaviano Labò (Enzo Grimaldo), Mignon Dunn (Laura Adorno), Aldo Protti (Barnaba), Norman Scott (Alvise Badoero), Luisa Bartoletti (La Cieca), Tulio Gagliardo (Zuàne), Italo Pasini (Isèpo), Guerrino Boschetti (Un cantore); Coro y Orquesta Estable del Teatro Colón; Carlo Felice Cillario, conductor [Recorded ‘live’ in the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 28 July 1970; Walhall Eternity Series WLCD 0337; 3 CDs, 200:28 (including Act One from a 1958 performance of Madama Butterfly); Available from  RICCARDO ZANDONAI (1883 – 1944): Francesca da Rimini, Opus 4—

RICCARDO ZANDONAI (1883 – 1944): Francesca da Rimini, Opus 4—