![CD REVIEW: Voices Victorious - Sony Classical discs featuring JONAS KAUFMANN (88875092492), OLGA PERETYATKO (8887507412), & MAURO PETER (88875083882) CD REVIEW: Voices Victorious - Sony Classical discs featuring JONAS KAUFMANN (88875092492), OLGA PERETYATKO (88875057412), & MAURO PETER (88875083882)]()

[1] GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Nessun dorma – The Puccini Album—Arias from Manon Lescaut, Le villi, Edgar, La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, La fanciulla del West, La rondine, Il tabarro, Gianni Schicchi, and Turandot—Jonas Kaufmann, tenor; Kristīne Opolais, soprano; Massimo Simeoli, baritone; Antonio Pirozzi, bass; Orchestra e Coro dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia; Sir Antonio Pappano, conductor [Recorded in Santa Cecilia Hall, Rome, Italy, 14 – 21 September 2014; Sony Classical 88875092492; 1 CD, time; Available from Amazon (USA), fnac (France), iTunes, jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

[2] GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868): Rossini!– Arias from Il viaggio a Reims, Matilde di Shabran, Tancredi, Semiramide, Il barbiere di Siviglia, and Il turco in Italia—Olga Peretyatko, soprano; Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna; Alberto Zedda, conductor [Recorded in Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Italy, 8 – 9, 11 – 12, and 14 – 15 November 2014; Sony Classical 88875057412; 1 CD, 70:22; Available from Amazon (USA), fnac (France), iTunes, jpc (Germany), and major music retailers]

[3] FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797 – 1828): Goethe Lieder—Mauro Peter, tenor; Helmut Deutsch, piano [Recorded in SRF Radiostudio Zürich Leutschenbach, Switzerland, 25 – 27 February 2015; Sony Classical 88875083882; 1 CD, 53:20; Available from Amazon (USA), iTunes, jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

If James Carville were entrusted with the management of an opera company, he might hang a sign somewhere in the theatre to remind his personnel of the principal focus of opera: the Voices, stupid. It is difficult to imagine any opera company deviating from this focus, but many institutions specializing in the performance of opera have in recent seasons offered their audiences Don Giovannis, Normas, Rigolettos, and Siegfrieds with pretty faces but the voices of Masettos, Clotildes, Marullos, and Mimes. It is not that there are no voices of quality to be heard on the world's stages today, but there is a worrying trend of valuing the package above the gift. Given the choice between an attractive visage and an unattractive one, the preference for the former is only natural, but in opera, as Shakespeare might have written, the voice is the thing. If she sounds like a menopausal shrew, of what use is a twenty-something Mimì with a Vogue-worthy face and figure? If opera is to survive, it must be sustained not by gimmicks or profusions of over-hyped waifs but by voices—properly-trained, thoughtfully-maintained, ably-projected voices. Neither a voice nor the body that houses it must be conventionally beautiful in order to communicate to audiences the emotions with which composers infused their scores: the beauty required to transform notes on a page into sounds that penetrate a listener's heart dwells in the imagination. There must be a voice supported by a properly-constructed technique at the service of that imagination, however, and three new discs from Sony Classical offer vastly different but equally compelling perspectives on the unique ways in which vocal music thrives in the new century. Truly significant voices have ever been rare, but these recordings dispel the oft-repeated allegation that they are now mere breaths away from extinction. Hype makes careers, but only voices of quality—voices like the three heard on these discs—distill the noises of living into the essence of song.

Considering his recent triumph with 'Nessun dorma' in the BBC Last Night of the Proms concert and the tremendous success of his Des Grieux in Munich, soon to be reprised at The Metropolitan Opera, the burgeoning splendors of the relationship between German tenor Jonas Kaufmann and the music of Giacomo Puccini are hardly surprising. It should not be thought that the relationship is a recent development, however: Kaufmann was an admired Rodolfo in La bohème in Zürich during the early years of his international career, he recorded Pinkerton opposite Angela Gheorghiu's Cio-Cio San for EMI, and his portrayal of Mario Cavaradossi in Tosca has been lauded in both Europe and America. With The Puccini Album, Kaufmann stakes his claim to being lauded as the preeminent Puccini tenor of the first quarter of the Twenty-First Century. There is no doubting that Kaufmann possesses an exceptionally good, perhaps even great voice and is an exceptionally good, perhaps even great singer. What must be discerned is his place in a tradition of Puccini singing extending back to Enrico Caruso. Kaufmann is fortunate in the context of this disc to enjoy the support of the Orchestra e Coro dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia and, particularly, Sir Antonio Pappano, as intuitive an interpreter of Puccini's music as there is at work today. Under Pappano's sympathetic leadership, the Santa Cecilia forces deliver robust but graceful performances, both instruments and voices balanced with discernible comprehension of textures and dramatic situations. Even in the microcosms of individual arias, Pappano exerts a guiding influence that discloses not only in-depth knowledge of the material but also, perhaps even more importantly, true affection for Puccini's often-criticized music.

Opening with music of which he has proved himself to be a masterful interpreter, Kaufmann makes of Des Grieux's lusciously tuneful 'Donna non vidi mai' from Manon Lescaut an intensely personal statement of blossoming attraction expressed through song. The top B♭ is no longer produced with the freedom of only a few seasons in past, but the top notes throughout the selections on The Puccini Album are ringing, secure, and on pitch—sadly, an achievement of which far too few tenors more than a decade into their careers can boast. Kaufmann is joined by his Munich (and scheduled MET) partner, Latvian soprano Kristīne Opolais in the scene 'Oh, sarò la più bella!' and the thrilling 'Tu, tu, amore? Tu?' Like Kaufmann, Opolais is on good form, but she lacks the tenor's intuitive feeling for Puccinian phrasing. Still, the effect of two strong voices in music like 'Ah! Manon, mi tradisce' is undeniably exciting. Kaufmann is partnered in the dramatic 'Presto! In fila!' and 'Ah! Non n'avvicinate' by Antonio Pirozzi, who voices both the Sergente's and the Capitano's lines with a resonant bass. In the course of these selections, Kaufmann manages to create a remarkably complete portrait of the impetuous, romantic Des Grieux, singing the music as well as any tenor has done since the heady days of Richard Tucker.

Completed in 1883, the 'opera-ballo'Le villi was Puccini's first work for the stage. Though clearly an early work, many of the hallmarks of Puccini's mature style are evident, not least his penchant for creating flowing melodies that surge above propulsive but generally unobtrusive orchestrations. Roberto's recitative 'Ei giunge!' and aria 'Torna ai felici dì' do not possess the melodic distinction of much of Puccini's later music for the tenor voice, but Kaufmann's singing is memorable, the voice's dark timbre elucidating nuances of the aria's text. Also an early work, Edgar deserves to be performed far more frequently despite the deficiencies of its libretto. In truth, the score is not top-drawer Puccini, but Kaufmann's burly, impassioned performance of the title character's 'Orgia, chimera dall'occhio vitreo' makes a powerful argument on the opera's behalf.

Opolais is Mimì to Kaufmann's Rodolfo in the duet that ends Act One of La bohème, 'O soave fanciulla.' Here, the coolness of the soprano's timbre lends the character that she portrays an aloofness that is not without charm, and though the style is still approximated the steadiness of tone counts for much. Kaufmann's voice is now an ungainly instrument for Rodolfo's music, but he sings poetically, shading his tone with the imagination of a young wordsmith in love. He preserves the lovely major-third harmony by preferring Puccini's written ending to the duet, eschewing the interpolated top C in unison with Mimì that brings many tenors to grief unnecessarily. Pirozzi is again heard with pleasure in the Sagrestano's interjections in Cavaradossi's 'Recondita armonia' from Act One of Tosca, captivatingly sung by Kaufmann. Baritone Massimo Simeoli sonorously supplies Sharpless's lines in Pinkerton's 'Addio, fiorito asil' from Act Three of Madama Butterfly. The melodic thrust of the aria perfectly suits Kaufmann, who intelligently uses the virility of his timbre to suggest greater vocal amplitude than he has at his command without forcing or shouting. Thankfully, he also leaves maudlin melodramatics to other tenors.

Kaufmann's Wiener Staatsoper performances of La fanciulla del West with Nina Stemme were justifiably acclaimed, and the excerpts from Johnson's music on The Puccini Album offer a tantalizing glimpse of his portrayal of the good-hearted bandito. The liquidity of his phrasing of 'Una parola sola!' and 'Or son sei mesi' lends the music an arresting element of vulnerability, and the contrasting energy and tenderness of his 'Risparmiate lo scherno' and 'Ch'ella mi creda libero,'complemented by Simeoli's rousingly machismo Rance, credibly elucidate both Johnson's ruggedness and his sensitivity. Kaufmann sang Ruggero in La rondine to great acclaim with Pappano at Covent Garden, and he and the conductor here collaborate on a pulse-quickening account of 'Parigi! È la città dei desideri.' The voice soars in ascending phrases as though the words were literally being hurled over the rooftops of Paris. Hearing Johnson's and Ruggero's music in succession, it is astonishing to note the differences between these creations of a composer often accused of stylistic stasis. It is also heartening to hear the music for both characters sung so handsomely and unaffectedly by the same singer.

Luigi's 'Hai ben ragione' from Il tabarro is an undervalued gem among Puccini's tenor arias, and the traversal that it receives from Kaufmann confirms its stature. Then, progressing to the final installment in Il trittico, he takes on Rinuccio's recitative 'Avete torto!' and familiar aria 'Firenze è come un albero fiorito' from Gianni Schicchi. It is again intriguing to hear both arias sung by the same singer, Luigi ideally requiring greater vocal heft than Rinuccio. Unexpectedly, 'Firenze è come in albero fiorito' is one of the finest selections on The Puccini Album. Kaufmann sings the aria with youthful ardor, leaving little doubt that Rinuccio's actions are motivated solely by his love for Lauretta. Aptly, the disc ends with the inevitable pair of Calàf's arias from Turandot. Opolais's reserve qualifies her as a near-ideal Liù, and her voice is at its loveliest in her few words in 'Non piangere, Liù,' to which Pirozzi contributes equally credibly as Timur. Kaufmann sings the aria superbly, shaping melodic units with a master craftsman's hand. His singing radiates compassion, and he depicts a Calàf hurt by the pain that his inability to requite her love causes Liù. Undoubtedly, more tenors have recorded 'Nessun dorma' who should not have done than have those for whom the aria is safe vocal territory. The aria's climactic top B is apparently irresistible even to singers who do not reliably have the note, but Kaufmann manages the range, high and low, with confidence if not true ease. The burnished, baritonal sound of the voice sustains Puccini's familiar melodic lines gloriously. Kaufmann's many admirers do him no favors by asserting that his vocalism is without flaws, but his singing on The Puccini Album is extraordinarily impressive, the work of a Puccini tenor with few peers in opera today.

![]()

An artist of any age could be mentored and conducted in the singing of music by Gioachino Rossini by no more authoritative an individual than Alberto Zedda. Neither his innate comprehension of the composer's idiom nor his zeal for advocating Rossini's music and stylistically-appropriate performances of it has been compromised by the advancing years, and whether in the lecture hall or on the podium he remains a seminal scholar and a persuasive interpreter of Rossini's operas. Presiding over the wholly idiomatic Orchestra and Chorus of Bologna's Teatro Comunale, he is the spine that supports Rossini!, this joyous disc featuring a sequence of glittering performances by Russian soprano Olga Peretyatko. The choristers and instrumentalists, clearly cognizant of being in the presence of a man who knows and loves the music of Rossini as intimately as the composer himself must have done, perform with the sort of dedication that elucidates the quality of the music. In Zedda's hands, every note has significance that is honored but not over-accentuated, and he nurtures the young soprano's prodigious gifts for singing Rossini arias with the glee of a doyen recognizing a kindred spirit.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Zedda does not use Rossini's trademark crescendi as a license to apply accelerandi to passages of rising tension and dramatic magnitude. Rather, the conductor meaningfully exhibits how Rossini cleverly used the device differently in comic and tragic scores. In the realm of ubiquitous Rossinian opera buffa, Peretyatko opens Rossini! with an ebullient account of Rosina's 'Una voce poco fa' from Act One of Il barbiere di Siviglia. Here and throughout the selections on this disc, Zedda's tempi sometimes initially seem ploddingly deliberate, but the seldom-appreciated felicities of Rossini's witty orchestrations that emerge and the soprano's appreciably clean negotiations of coloratura are facilitated by the conductor's approach. Still a young singer, Peretyatko does not yet possess Jonas Kaufmann's ability to fully characterize a part in the context of a singer aria, but she sings the Rossinian ladies' music with feeling and consummate style. Though composed for a contralto, Rosina has often been usurped by sopranos, in some cases—Lily Pons, Beverly Sills, and Diana Damrau, for instance—charmingly. With a smile in the voice, Peretyatko dispatches the coloratura accurately and sparklingly. Though her diction is generally fine, her textual inflections are not quite idiomatic. The voice records well, but the overtones that make the instrument effervescent in the opera house are only partially in evidence on disc. She is nonetheless a perky, pretty Rosina who is equally lovable in docility and mischief.

Fiorilla's aria 'I vostri cenci vi mando' from Il turco in Italia is also an excellent vehicle for both Peretyatko and Zedda. Throughout the performances on Rossini!, the soprano complements the conductor's stylistic mastery by ornamenting tastefully—a significant departure from the model of Sills!—and, despite the reliability of her starlit upper register, rejecting stratospheric interpolated top notes at the ends of arias. Her center of vocal gravity is slightly higher than that of many Fiorillas, among whose ranks on recordings are singers as different as Maria Callas, Montserrat Caballé, Sumi Jo, and Cecilia Bartoli, but her comfort with the tessitura is apparent. Like her 'Una voce poco fa,' her account of Fiorilla's aria fizzes with both femininity and feistiness, amplified by Zedda's sympathetic accompaniment.

In its plot and the incredible demands of its casting, Il viaggio a Reims is an opera that both depicts and is a festive occasion. Rossini loaded the score of Il viaggio with fantastic music, and any opportunity to hear selections from the opera sung as well as they are sung on this disc is self-recommending. First, Peretyatko voices Corinna's aria d'improvviso'All'ombra amena' with an apt air of spontaneity, the voice and the singer's demeanor glowing more in each successive phrase. An amusing suggestion of mock opera seria exasperation enlivens her singing of Contessa di Folleville's 'Partir, o ciel!' The aria's filigree is delicately drawn by Peretyatko, but she mostly paints with primary colors, depicting an appropriately two-dimensional Contessa of limited capacity for empathy but boundless fun. The difficulties of the music hold no terrors for her, and the combination of bravura solidity and insouciant haughtiness is ideal for the character. How marvelous she would surely be as Comtesse Adèle in Le comte Ory!

Matilde di Shabran, in which opera Peretyatko triumphed opposite Juan Diego Flórez at Pesaro’s Rossini Opera Festival, is, like Il viaggio a Reims, an infrequent visitor to recording studios, so this souvenir of Peretyatko's interpretation of the title rôle is especially welcome. She shapes the recitative 'Ami alfine' with considerable eloquence that she expands further in her singing of the lovely aria 'Tacea la tromba altera.' Peretyatko's experience with performing this music on stage is unmistakable, not least in her expertly-judged phrasing. Obvious, too, is the intuition for Rossini's serious music that she has acquired via acclaimed performances of the rôle of Desdemona in Rossini's Otello. The bravura demands of Matilde's aria are met with confidence to spare, but it is the spirit of the singing that is most impressive. The sapphire hues in the voice that glimmer evocatively in comic music take on darker tints in more dire contexts, and the animated girl who earlier brought the wily Rosina and Fiorilla to life unexpectedly becomes a woman of radiant maturity.

The title character's aria 'Bel raggio lusinghier' from Semiramide is one of Rossini's most familiar numbers and, in truth, a prime instance of the composer's genius overcoming the banality of the tune. The performance of the aria on this disc benefits greatly from Peretyatko's firm technical footing, but there are a few passages in which the tone lacks focus, as though the coloratura displaces the core of her singing. Still, she sings the aria unaffectedly, and her performance, likely closer in vocal amplitude to what Rossini expected than several modern exponents of Semiramide like Dame Joan Sutherland and Cheryl Studer, is beguiling. Musically and dramatically, Amenaide's scena'Di mia vita infelice' and aria 'No, che il morir' from Tancredi constitute the best selection on Rossini!, and the traversal that this music receives from Peretyatko and Zedda is equal to the splendor of Rossini's creation. Here, the character's emotions rush to the surface, and the youthful soprano limns them simply but touchingly. She and Zedda approach the music without heaviness or exaggeration, meticulously maintaining the buoyancy of the melodic line. Ultimately, it is particularly fitting that the disc is entitled Rossini!, for it is the composer's music that is front and center here. An artist as committed to the study, understanding, and informed performance of Rossini's music as Alberto Zedda would have it no other way; neither would Olga Peretyatko, who pursues personal expression rather than rigid perfection and in doing so gives as enjoyable a recital of Rossini arias as has been recorded in recent years.

![]()

It is no hyperbole to suggest that the wholly organic familiarity exhibited in the music of Rossini by Alberto Zedda is paralleled in German Lieder repertory by pianist Helmut Deutsch, a collaborative artist of the first order whose playing has enriched the recitals and recordings of many of the past quarter-century's most accomplished exponents of Lieder singing. Schubert Lieder are for Deutsch their own language, and he is among the few artists who 'speak' it without distractingly idiosyncratic accents. With Deutsch as his guide, young Swiss tenor Mauro Peter is rapidly attaining fluency. He has to his credit a beautiful voice notable for the evenness of the integration of the upper and lower registers and an alluring plangency of timbre: in opera and Lieder, his tones combine the steel of Kaufmann with the sweetness of his countryman Ernst Haefliger. As an interpreter of Schubert Lieder, he is establishing himself as a steward of the tradition of Anton Dermota, Haefliger, and Peter Schreier, singers for whom music and poetry were inseparable. There is in Peter's singing on this disc a strong element of the troubadour: though there is no shortage of power when it is needed, these performances seem directed to the individual listener instead of the recital hall. Peter and Deutsch initiate a conversation with Schubert into which the listener is invited. Whether or not one knows German, this is a recital that makes its points sonorously and causes merely listening to seem like actively taking part.

The influence exerted by the work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in both opera houses and recital halls cannot be overstated. The publication and widespread distribution of Die Leiden des jungen Werther and Faust in the final thirty years of the Eighteenth Century triggered a creative avalanche of a magnitude rivaled in music only by the bodies of work inspired by the Bible, Shakespeare, Schiller, and Sir Walter Scott. Of special resonance for composers was Goethe's philosophical handling of the bargain between Faust and Satan, which abounds with artistic implications. No less momentous as sources of inspiration for composers were Goethe's smaller-scaled works, in many of which the ethos of the epic texts found varied contexts. Among the composers who turned to Goethe's words for Lieder texts, no one was more successful at capturing the essence of a passage than Schubert. Frequently employing verses by his contemporaries, Schubert had an extraordinary gift for elevating texts beyond their literary merit, but he found in Goethe's lines words for the most part worthy of his genius. Both writer and composer find in Peter and Deutsch performers who convey a full appreciation of how special the Goethe settings are among Schubert's Lieder.

Opening with the exquisitely-written 'Ganymed' (D. 544), Peter sings with tonal sheen befitting a youth with whom a god became besotted. Throughout this recital, the tenor does not shrink from overt Romanticism, basking in rather than hiding from the songs' innate sensuality and even hinting at a subdued eroticism that lurks beneath the surface. His ambiguous, searching voicing of 'Erster Verlust' (D. 226) is bolstered by Deutsch's suggestive playing. The disquieting tranquility with which Peter sings 'Rastlose Liebe' (D. 138) is strangely haunting, the sound of the voice taking on a disembodied quality that floats over the piano's firm tones like mist settling menacingly on a bucolic landscape. Subtlety is also the hallmark of Peter's and Deutsch's performance of 'Meeres Stille' (D. 216). The effects that the tenor is able to achieve with his exemplary breath control disclose the marvels of Schubert's construction of melodic arcs, and his clear, vibrant diction enables the listener to appreciate the insightfulness with which the composer melded Goethe's words with his music.

The three Gesänge des Harfners (Opus 12) are here presented with the unity of a Lieder cycle in miniature, singer and pianist exploring the commonalities among the songs without extrapolating contexts that neither text nor music supports. 'Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt' (D. 478) is sung with appropriately-scaled intensity, and Peter's account of 'Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen' (D. 479) is characterized by a profoundly moving but not overwhelming melancholy. In 'An die Türen will ich schleichen' (D. 480), it is the beauty of the voice that is most impressive: when the words are caressed by such nobly-produced tone, what more is required?

'Der Musensohn' (D. 764) is among Schubert's most beautiful songs, and Peter's performance of it warrants comparison with the finest recordings. On disc, only Hermann Prey equals Peter in the practice of the now-elusive art of choosing Lieder from Schubert's extensive catalogue that are ideal for his individual voices, literal and interpretive. Among his fellow tenors, it is the golden-toned Russian Georgi Vinogradov that Peter's aristocratic but flexible singing on this disc most recalls. The drama in 'Der König in Thule' (D. 367), 'Heidenröslein' (D. 257), and 'Der Fischer' (D. 225) is brought to the foreground without being given excessive prominence. Deutsch's strongly-defined pianism drives ‘Der König in Thule,' and Peter takes the lead in ‘Heidenröslein,' the voice unfurled in a grand canopy of melody. 'Erlkönig' (D. 328) is one of the most familiar of Schubert's Goethe settings, but Peter sings it as though the newly-completed manuscript were handed to him moments before he stepped up to Sony's microphone. 'Am Flusse' (D. 766) and 'An den Mond' (D. 296) are fastidiously differentiated by tenor and pianist alike, and the element of awe that they impart in the oft-abused 'Wanderers Nachtlied' (D. 768) lends the song an immediacy that many interpreters miss.

The quartet of songs at the end of the disc draw from Peter and Deutsch interpretations of unmistakable affection. The too-little-heard 'Versunken' (D. 715), a jewel of Schubert's imagination, is very movingly done, the mood of the piece extracted from the text rather than artificially imposed by the performers. Likewise, the singular sentiments of 'Geheimes' (D. 719) are limned with the simplicity that is possible only with careful study and absorption of the music. 'An die Entfernte' (D. 765) flows in an uninterrupted torrent of expressivity that floods the work of both Peter and Deutsch, expanding but not diluting the gentlemen's consummate musicality. The sublime 'Willkommen und Abschied' (D. 767) is a fitting conclusion for a Goethe-themed disc, and Peter and Deutsch devote to their performance of it the very best of their artistries. Tenor and pianist trace the lines of the music with such cooperation that their efforts seem to be those of a single artist. Deutsch's accomplishments in Lieder repertory are too extensive to require further endorsement, but Mauro Peter here proves himself to be a Schubertian of comprehensive musical and poetic excellence. Especially in the last years of his life, the increasingly curmudgeonly Goethe was suspicious of and even openly hostile to musical settings of his texts. To what could he have objected in Schubert's Lieder had he heard Peter and Deutsch perform them?

The musical legacies of the Twenty-First Century are only just beginning to take shape, but the lessons of recent years are many and often learned only after bitterness and pride are vanquished. For those who can neither fathom nor endure a world without Classical Music, there are lessons that must be taken to heart. These three Sony Classical discs offer a blueprint for building a secure, satisfying future for an art for which many commentators have already written obituaries. It is sadly true that Tucker, Sills, and Wunderlich no longer grace the world's stages today, but there are in this new millennium artists of the caliber of Jonas Kaufmann, Olga Peretyatko, and Mauro Peter. What makes opera and Classical vocal music relevant for modern audiences? Voices such as these, stupid!

HENRY PURCELL (1659 – 1695) and DANIEL PURCELL (1664 – 1717): The Purcells– Vocal Works with Basso continuo—Delia Agúndez, soprano; Manuel Minguillón, archlute and Baroque guitar; Laura Puerto, harpsichord and organ; Ruth Verona, cello [Recorded in el Aula de Música de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Spain, in September 2014; enchiriadis EN 2042; 1 CD, 53:01; Available from ClassicsOnline HD, Amazon, and major music retailers]

HENRY PURCELL (1659 – 1695) and DANIEL PURCELL (1664 – 1717): The Purcells– Vocal Works with Basso continuo—Delia Agúndez, soprano; Manuel Minguillón, archlute and Baroque guitar; Laura Puerto, harpsichord and organ; Ruth Verona, cello [Recorded in el Aula de Música de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Spain, in September 2014; enchiriadis EN 2042; 1 CD, 53:01; Available from ClassicsOnline HD, Amazon, and major music retailers] WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791): Don Giovanni, K. 527—William Dooley (Don Giovanni), Donald Gramm (Leporello), Beverly Sills (Donna Anna), Michel Sénéchal (Don Ottavio), Brenda Lewis (Donna Elvira), Laurel Hurley (Zerlina), Robert Trehy (Masetto), Ernest Triplett (Il Commendatore), McHenry Boatwright (la Statua); Chorus and Orchestra of the Opera Company of Boston; Sarah Caldwell, conductor [Recorded ‘live’ in performance in the Boston Opera House on 21 February 1966;

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791): Don Giovanni, K. 527—William Dooley (Don Giovanni), Donald Gramm (Leporello), Beverly Sills (Donna Anna), Michel Sénéchal (Don Ottavio), Brenda Lewis (Donna Elvira), Laurel Hurley (Zerlina), Robert Trehy (Masetto), Ernest Triplett (Il Commendatore), McHenry Boatwright (la Statua); Chorus and Orchestra of the Opera Company of Boston; Sarah Caldwell, conductor [Recorded ‘live’ in performance in the Boston Opera House on 21 February 1966;  GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Turandot [Completion by Franco Alfano]—

GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Turandot [Completion by Franco Alfano]— WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791): Die Entführung aus dem Serail, K. 384—

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791): Die Entführung aus dem Serail, K. 384— GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Simon Boccanegra—

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Simon Boccanegra— [1] ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841 – 1904): Alfred, B. 16—

[1] ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841 – 1904): Alfred, B. 16—

RICHARD STRAUSS (1864 – 1949): Die Frau ohne Schatten, Opus 65—

RICHARD STRAUSS (1864 – 1949): Die Frau ohne Schatten, Opus 65—![IN REVIEW: Mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY in the title rôle of Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY in the title rôle of Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-NlTg2feudq4/VeH6MRHW_lI/AAAAAAAAFBQ/o6Rm7x67jXA/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520095%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868): La Cenerentola, ossia La bontà in trionfo—

GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868): La Cenerentola, ossia La bontà in trionfo—![IN REVIEW: Soprano JULIE CELONA-VANGORDEN as Clorinda (left) and mezzo-soprano CLARA O'BRIEN as Tisbe (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Soprano JULIE CELONA-VANGORDEN as Clorinda (left) and mezzo-soprano CLARA O'BRIEN as Tisbe (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-NXu3dDm_aAc/VeH6NIN5P1I/AAAAAAAAFBY/yudPixFWRh8/Clorinda-Tisbe%25255B11%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Sorelle [not so] simpatiche: Soprano Julie Celona-VanGorden as Clorinda (left) and mezzo-soprano Clara O’Brien as Tisbe (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

Sorelle [not so] simpatiche: Soprano Julie Celona-VanGorden as Clorinda (left) and mezzo-soprano Clara O’Brien as Tisbe (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![IN REVIEW: Bass-baritone TIMOTHY JONES (center) as Alidoro in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Bass-baritone TIMOTHY JONES (center) as Alidoro in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-30UBQBSVVM4/VeH6NytsijI/AAAAAAAAFBg/kbFHwXIcRTo/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520082%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Alla testa della classe: Bass-baritone Timothy Jones as Alidoro (center) in Greensboro Opera’s production of Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

Alla testa della classe: Bass-baritone Timothy Jones as Alidoro (center) in Greensboro Opera’s production of Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![IN REVIEW: Bass-baritone DONALD HARTMANN as Don Magnifico (left) and mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY as Angelina (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Bass-baritone DONALD HARTMANN as Don Magnifico (left) and mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY as Angelina (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-2cxKqkK_92Q/VeH6OYBL3iI/AAAAAAAAFBo/jMa2r1oC5-0/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520101%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Padre e figlia: Bass-baritone Donald Hartmann as Don Magnifico (left) and mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy as Angelina (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

Padre e figlia: Bass-baritone Donald Hartmann as Don Magnifico (left) and mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy as Angelina (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![IN REVIEW: Baritone SIDNEY OUTLAW as Dandini (left) and tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Baritone SIDNEY OUTLAW as Dandini (left) and tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-QpI_kXyX1Cs/VeH6PMMaJiI/AAAAAAAAFBw/Ou7u3yxqsrA/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520066%25255B16%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Il Principe ed il suo valletto: Baritone Sidney Outlaw as Dandini (left) and tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

Il Principe ed il suo valletto: Baritone Sidney Outlaw as Dandini (left) and tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![IN REVIEW: Tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-0jE21d90jCw/VeH6P2BIxBI/AAAAAAAAFB4/lhhvDLlKpz8/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520045%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Do di petto: Tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

Do di petto: Tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![IN REVIEW: Tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro (left) and mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY in the title rôle (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro (left) and mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY in the title rôle (right) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-CJip-AF9faU/VeH6QjrXp7I/AAAAAAAAFCA/6DeKmk3Dv9E/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520110%25255B7%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) La bontà in trionfo: Tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro (left) and mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy as Angelina (right) in Greensboro Opera’s production of Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

La bontà in trionfo: Tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro (left) and mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy as Angelina (right) in Greensboro Opera’s production of Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![IN REVIEW: Mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY as Angelina (left), tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro (center), and baritone SIDNEY OUTLAW as Dandini (left) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission] IN REVIEW: Mezzo-soprano SANDRA PIQUES EDDY as Angelina (left), tenor ANDREW OWENS as Don Ramiro (center), and baritone SIDNEY OUTLAW as Dandini (left) in Greensboro Opera's production of Gioachino Rossini's LA CENERENTOLA, August 2015 [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-BVJlsCBHG4c/VeH6Rd2rE_I/AAAAAAAAFCI/eiOVngiJ-UE/APG-1448-2%252520Cinderella%252520100%25255B6%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) In un nodo di perplessità: Mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy as Angelina (left), tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro (center), and baritone Sidney Outlaw as Dandini (right), with (from left to right) soprano Julie Celona-VanGorden as Clorinda, mezzo-soprano Clara O’Brien as Tisbe, and bass-baritone Donald Hartmann as Don Magnifico visible at the rear, in Greensboro Opera’s production of Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]

In un nodo di perplessità: Mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy as Angelina (left), tenor Andrew Owens as Don Ramiro (center), and baritone Sidney Outlaw as Dandini (right), with (from left to right) soprano Julie Celona-VanGorden as Clorinda, mezzo-soprano Clara O’Brien as Tisbe, and bass-baritone Donald Hartmann as Don Magnifico visible at the rear, in Greensboro Opera’s production of Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola [Photo © by Artisan Images/David Wilson, used with permission]![CD REVIEW: ARIAS FOR LUIGI MARCHESI - Ann Hallenberg, mezzo-soprano [Glossa GCD 923505] CD REVIEW: ARIAS FOR LUIGI MARCHESI - Ann Hallenberg, mezzo-soprano [Glossa GCD 923505]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-492-81a2L_E/VePDza7tzJI/AAAAAAAAFCg/_mtoBc0c6Mo/Arias-for-Luigi-Marchesi_Ann-Hallenb%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) FRANCESCO BIANCHI (1752 – 1810), LUIGI CHERUBINI (1760 – 1842), DOMENICO CIMAROSA (1749 – 1801), JOHANN SIMON MAYR (1763 – 1845), JOSEF MYSLIVEČEK (1737 – 1781), GAETANO PUGNANI (1731 – 1798), GIUSEPPE SARTI (1729 – 1802), and NICCOLÒ ANTONIO ZINGARELLI (1752 – 1837): Arias for Luigi Marchesi– The Great Castrato of the Napoleonic Era—

FRANCESCO BIANCHI (1752 – 1810), LUIGI CHERUBINI (1760 – 1842), DOMENICO CIMAROSA (1749 – 1801), JOHANN SIMON MAYR (1763 – 1845), JOSEF MYSLIVEČEK (1737 – 1781), GAETANO PUGNANI (1731 – 1798), GIUSEPPE SARTI (1729 – 1802), and NICCOLÒ ANTONIO ZINGARELLI (1752 – 1837): Arias for Luigi Marchesi– The Great Castrato of the Napoleonic Era—![CD REVIEW: Marchesi miracle workers - Conductor STEFANO ARESI (left) and mezzo-soprano ANN HALLENBERG (right), photographed by Minjas Zugik [Photo © 2015 by Minjas Zugik; used with permission] CD REVIEW: Marchesi miracle workers - Conductor STEFANO ARESI (left) and mezzo-soprano ANN HALLENBERG (right), photographed by Minjas Zugik [Photo © 2015 by Minjas Zugik; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-qfzn49-AiGQ/VePD0GERC3I/AAAAAAAAFCo/1Z5EUSVlPyo/Aresi-Hallenberg_Marchesi-CD_Minjas-.jpg?imgmax=800) Marchesi miracle workers: Conductor Stefano Aresi (left) and mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenberg (right), photographed by Minjas Zugik [Photo © 2015 by Minjas Zugik; used with permission]

Marchesi miracle workers: Conductor Stefano Aresi (left) and mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenberg (right), photographed by Minjas Zugik [Photo © 2015 by Minjas Zugik; used with permission]![ARTS IN ACTION: Opera Carolina's 2015 - 2016 Season poised to thrill [Opera Carolina graphic © by Opera Carolina, all rights reserved] ARTS IN ACTION: Opera Carolina's 2015 - 2016 Season poised to thrill [Opera Carolina graphic © by Opera Carolina, all rights reserved]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-G2UmlVdAPic/VesmvGqMj6I/AAAAAAAAFDM/dXkReP65QC4/Opera-Carolina_Logo%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) It is not solely owing to its association with the consort of King George III that Charlotte is known as the Queen City. In past seasons, ladies wielding vocal crowns—ladies like Lisa Daltirus and Denyce Graves, Leonora and Azucena in the 2011 production of Verdi’s Il trovatore, Brenda Harris, Abigaille in 2014’s Nabucco, and Othalie Graham and Dina Kuznetsova, the eponymous Princess and Liù in 2015’s Turandot—have lent Charlotte’s regal epithet an added layer of meaning. Thanks to the endeavors of these artists and their colleagues at

It is not solely owing to its association with the consort of King George III that Charlotte is known as the Queen City. In past seasons, ladies wielding vocal crowns—ladies like Lisa Daltirus and Denyce Graves, Leonora and Azucena in the 2011 production of Verdi’s Il trovatore, Brenda Harris, Abigaille in 2014’s Nabucco, and Othalie Graham and Dina Kuznetsova, the eponymous Princess and Liù in 2015’s Turandot—have lent Charlotte’s regal epithet an added layer of meaning. Thanks to the endeavors of these artists and their colleagues at ![ARTS IN ACTION: Opera Carolina's 2015 - 2016 Season poised to thrill [Opera Carolina graphic © by Opera Carolina, all rights reserved] ARTS IN ACTION: Opera Carolina's 2015 - 2016 Season poised to thrill [Opera Carolina graphic © by Opera Carolina, all rights reserved]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-C49G623uMV4/VesmviGFPhI/AAAAAAAAFDQ/sOvdr4aP_NE/Opera-Carolina_2015-2016_Promo-2%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![ARTS IN ACTION: Opera Carolina's 2015 - 2016 Season poised to thrill [Opera Carolina graphic © by Opera Carolina, all rights reserved] ARTS IN ACTION: Opera Carolina's 2015 - 2016 Season poised to thrill [Opera Carolina graphic © by Opera Carolina, all rights reserved]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-RSRgpD4fdHs/VesmwGCgdpI/AAAAAAAAFDc/ir7f7pZ0hNI/Opera-Carolina_2015-2016_Promo%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) All casting is subject to change without notice. Graphics © by Opera Carolina; all rights reserved.

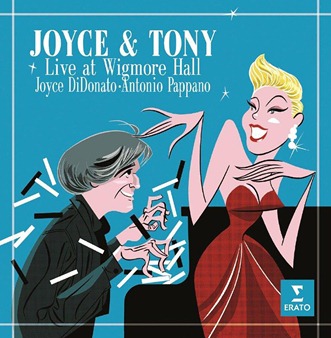

All casting is subject to change without notice. Graphics © by Opera Carolina; all rights reserved. FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732 – 1809), GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868), FRANCESCO SANTOLIQUIDO (1883 – 1971), ERNESTO DE CURTIS (1875 – 1937), et. al.: Joyce & Tony Live at Wigmore Hall—

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732 – 1809), GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 – 1868), FRANCESCO SANTOLIQUIDO (1883 – 1971), ERNESTO DE CURTIS (1875 – 1937), et. al.: Joyce & Tony Live at Wigmore Hall— GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Tosca—Tamara Milashkina (Floria Tosca), Vladimir Atlantov (Mario Cavaradossi), Yuri Mazurok (Barone Scarpia), Valeri Yaroslavtsev (Cesare Angelotti), Vitali Nartov (Il sagrestano), Andrei Sokolov (Spoletta), Vladimir Filippov (Sciarrone), Mikhail Shkaptsov (Un carceriere), Alexander Pavlov (Un pastore); Choir and Orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre; Mark Ermler, conductor [Recorded in the Bolshoi Theatre in 1974;

GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 – 1924): Tosca—Tamara Milashkina (Floria Tosca), Vladimir Atlantov (Mario Cavaradossi), Yuri Mazurok (Barone Scarpia), Valeri Yaroslavtsev (Cesare Angelotti), Vitali Nartov (Il sagrestano), Andrei Sokolov (Spoletta), Vladimir Filippov (Sciarrone), Mikhail Shkaptsov (Un carceriere), Alexander Pavlov (Un pastore); Choir and Orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre; Mark Ermler, conductor [Recorded in the Bolshoi Theatre in 1974;  [1] ROMAN BERGER (born 1930): Pathetique (2006), Sonata No. 3 ‘da camera’ (1971), Allegro frenetico con reminiscenza (2006), Impromptu (2013), and Epilogue (Omaggio a L. v. B.) (2010)—

[1] ROMAN BERGER (born 1930): Pathetique (2006), Sonata No. 3 ‘da camera’ (1971), Allegro frenetico con reminiscenza (2006), Impromptu (2013), and Epilogue (Omaggio a L. v. B.) (2010)—

![PERFORMANCE REVIEW: Giuseppe Verdi's DON CARLO at Wichita Grand Opera, 27 September 2015 [Image: Costume design for Filippo II in the Teatro alla Scala production of Verdi's revised version of the score in four acts, 1884] PERFORMANCE REVIEW: Giuseppe Verdi's DON CARLO at Wichita Grand Opera, 27 September 2015 [Image: Costume design for Filippo II in the Teatro alla Scala production of Verdi's revised version of the score in four acts, 1884]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-lFLuxC5tmVo/VgxFbQ23H3I/AAAAAAAAFJg/x5GnRK9gJaM/Ricordi-Don-Carlo_Filippo3.jpg?imgmax=800) GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Don Carlo [1882 – 1883 La Scala version in four acts]—

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Don Carlo [1882 – 1883 La Scala version in four acts]— ALBAN BERG (1885 – 1935): Lyrische Suite [with alternate version of Largo desolato movement with soprano]; EGON WELLESZ (1885 – 1974): Sonette der Elisabeth Barrett Browning, Opus 52; and ERIC ZEISL (1905 – 1959): ‘Komm, süßer Tod’ [arranged for soprano and string quartet by J. Peter Koene]—

ALBAN BERG (1885 – 1935): Lyrische Suite [with alternate version of Largo desolato movement with soprano]; EGON WELLESZ (1885 – 1974): Sonette der Elisabeth Barrett Browning, Opus 52; and ERIC ZEISL (1905 – 1959): ‘Komm, süßer Tod’ [arranged for soprano and string quartet by J. Peter Koene]—

All casting is subject to change without notice. Graphics © by North Carolina Opera; all rights reserved.

All casting is subject to change without notice. Graphics © by North Carolina Opera; all rights reserved. [1] WITOLD LUTOSŁAWSKI (1913 – 1994): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra / Koncert na fortepian i orkiestrę (1987 – 88) and Symphony No. 2 / II Symfonia (1965 – 67)—Krystian Zimerman, piano;

[1] WITOLD LUTOSŁAWSKI (1913 – 1994): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra / Koncert na fortepian i orkiestrę (1987 – 88) and Symphony No. 2 / II Symfonia (1965 – 67)—Krystian Zimerman, piano;

![IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor RENÉ BARBERA as il Duca di Mantova (left) and soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Christina Holcomb Photography, LLC; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor RENÉ BARBERA as il Duca di Mantova (left) and soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Christina Holcomb Photography, LLC; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-HpWLd0yRp9A/VisRCjCFROI/AAAAAAAAFMQ/D6N484_xFOg/Rigoletto-35-of-86-T-2LOW4.jpg?imgmax=800) GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Rigoletto—

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Rigoletto—![IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano KRISTIN SCHWECKE as Maddalena in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano KRISTIN SCHWECKE as Maddalena in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-QUszxN638hw/VisRDWtRoWI/AAAAAAAAFMU/_7sQzh0fyc0/Rigoletto_Schwecke_Traci-Arney-Photo.jpg?imgmax=800) Bella figlia dell’amore: Soprano Kristin Schwecke as Maddalena in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]

Bella figlia dell’amore: Soprano Kristin Schwecke as Maddalena in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-BzgMA-MlFMU/VisRD7_5CzI/AAAAAAAAFMg/7bdsccju1j4/Rigoletto_Maples_Traci-Arney-Photogr.jpg?imgmax=800) Bella salvatrice: Soprano Amy Maples as Gilda in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]

Bella salvatrice: Soprano Amy Maples as Gilda in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Bass-baritone BRIAN BANION as Sparafucile in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Bass-baritone BRIAN BANION as Sparafucile in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-R2liJLrNoCw/VisREeJCweI/AAAAAAAAFMk/O-NxKsc_u3o/Rigoletto_Banion_Traci-Arney-Photogr%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Assassino sonoro: Bass-baritone Brian Banion as Sparafucile in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]

Assassino sonoro: Bass-baritone Brian Banion as Sparafucile in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor RENÉ BARBERA as il Duca di Mantova in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor RENÉ BARBERA as il Duca di Mantova in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-rr0uPVyk-28/VisRE3SLbgI/AAAAAAAAFMs/yjGIGnG4bBc/Rigoletto_Barbera_Traci-Arney-Photog%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Duca seducente: Tenor René Barbera as il Duca di Mantova in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]

Duca seducente: Tenor René Barbera as il Duca di Mantova in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda (left) and tenor RENÉ BARBERA as il Duca di Mantova (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Christina Holcomb Photography, LLC; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda (left) and tenor RENÉ BARBERA as il Duca di Mantova (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Christina Holcomb Photography, LLC; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-dFQzwtomgl8/VisRFcoDLqI/AAAAAAAAFM0/1fteBv-zir4/Rigoletto-12-of-86-LOW6.jpg?imgmax=800) Speranza ed anima sol tu sarai per me: Soprano Amy Maples as Gilda (left) and tenor René Barbera as il Duca di Mantova (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Christina Holcomb Photography, LLC; used with permission]

Speranza ed anima sol tu sarai per me: Soprano Amy Maples as Gilda (left) and tenor René Barbera as il Duca di Mantova (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Christina Holcomb Photography, LLC; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Baritone ROBERT OVERMAN as Rigoletto (left) and soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Baritone ROBERT OVERMAN as Rigoletto (left) and soprano AMY MAPLES as Gilda (right) in Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-utqy_rPxoog/VisRF8HK9kI/AAAAAAAAFM8/OrpCblAudmY/Rigoletto_Overman-Maples_Traci-Arney.jpg?imgmax=800) Padre e figlia: Baritone Robert Overman as Rigoletto (left) and soprano Amy Maples as Gilda (right) in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]

Padre e figlia: Baritone Robert Overman as Rigoletto (left) and soprano Amy Maples as Gilda (right) in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Baritone ROBERT OVERMAN in the title rôle of Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Bartione ROBERT OVERMAN in the title rôle of Piedmont Opera's production of Giuseppe Verdi's RIGOLETTO, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-vkW1q6mjYQQ/VisRGddMMVI/AAAAAAAAFNE/yO8Ah4MJGkE/Rigoletto_Overman_Traci-Arney-Photog%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Pari siamo: Baritone Robert Overman in the title rôle in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]

Pari siamo: Baritone Robert Overman in the title rôle in Piedmont Opera’s production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, October 2015 [Photo © by Traci Arney Photography; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: The cast of Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina] IN PERFORMANCE: The cast of Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-Ou6U5AZz0zo/Vi4ldGiaHKI/AAAAAAAAFNc/aPRuLuaFdes/IMG_1086e4.jpg?imgmax=800) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827): Fidelio, Opus 72—

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827): Fidelio, Opus 72—![IN PERFORMANCE: The Company of Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: The Company of Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-4vmGBePd1MA/Vi4ld0HW76I/AAAAAAAAFNk/sqtdEKqPDHY/3Y6A1128e%25255B10%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) O welch ein Augenblick: the Company of Opera Carolina’s production of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]

O welch ein Augenblick: the Company of Opera Carolina’s production of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano MARIA KATZARAVA as Leonore in Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Soprano MARIA KATZARAVA as Leonore in Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-jjr_bBhXvhI/Vi4leA2-kvI/AAAAAAAAFNo/A1FDyJf2ibs/IMG_0703ee%25255B11%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Sein Weib: Soprano Maria Katzarava as Leonore in Opera Carolina’s production of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]

Sein Weib: Soprano Maria Katzarava as Leonore in Opera Carolina’s production of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]![IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor ANDREW RICHARDS as Florestan (left) and soprano MARIA KATZARAVA as Leonore (right) in Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission] IN PERFORMANCE: Tenor ANDREW RICHARDS as Florestan (left) and soprano MARIA KATZARAVA as Leonore (right) in Opera Carolina's production of Ludwig van Beethoven's FIDELIO, October 2015 [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-LG6_HtUhZOo/Vi4leiRJYeI/AAAAAAAAFNw/HylXESmYGts/3Y6A1039e8.jpg?imgmax=800) Die Macht der Hoffnung: Tenor Andrew Richards as Florestan (left) and soprano Maria Katzarava as Leonore (right) in Opera Carolina’s production of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]

Die Macht der Hoffnung: Tenor Andrew Richards as Florestan (left) and soprano Maria Katzarava as Leonore (right) in Opera Carolina’s production of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio [Photo by Jon Silla, © by Opera Carolina; used with permission]