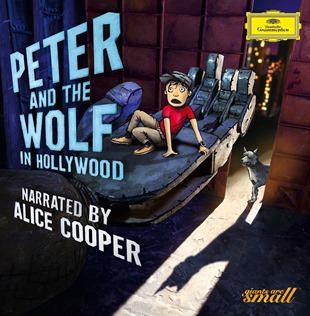

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 – 1953): Peter and the Wolf, Opus 67, plus music by Paul Dukas, Sir Edward Elgar, Edvard Grieg, Gustav Mahler, Modest Mussorgsky, Giacomo Puccini, Erik Satie, Robert Schumann, Bedřich Smetana, Richard Wagner, and Alexander von Zemlinsky—Alice Cooper, narrator; Bundesjugendorchester; Alexander Shelley, conductor [Recorded in Probenstudio Stolberger Straße, Cologne, Germany, during April 2014 (Peter and the Wolf), Funkhaus Berlin Nalepastraße, Germany, during September 2014 (other musical excerpts), and 5A Studios, London, UK, during June 2015 (narration); Deutsche Grammophon 479 4888 (also available with narration in German by Campino, 479 4894); 1 CD, 49:34; Available from DGG, Amazon (USA), jpc (Germany - English version | German version), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 – 1953): Peter and the Wolf, Opus 67, plus music by Paul Dukas, Sir Edward Elgar, Edvard Grieg, Gustav Mahler, Modest Mussorgsky, Giacomo Puccini, Erik Satie, Robert Schumann, Bedřich Smetana, Richard Wagner, and Alexander von Zemlinsky—Alice Cooper, narrator; Bundesjugendorchester; Alexander Shelley, conductor [Recorded in Probenstudio Stolberger Straße, Cologne, Germany, during April 2014 (Peter and the Wolf), Funkhaus Berlin Nalepastraße, Germany, during September 2014 (other musical excerpts), and 5A Studios, London, UK, during June 2015 (narration); Deutsche Grammophon 479 4888 (also available with narration in German by Campino, 479 4894); 1 CD, 49:34; Available from DGG, Amazon (USA), jpc (Germany - English version | German version), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

Neither recording Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf with narrations provided by celebrities of all artistic (and non-artistic) varieties nor reimagining Classics with the goal of making them more accessible for Twenty-First-Century audiences is uncommon, but neither endeavor has produced results more delightful than Deutsche Grammophon’s Peter and the Wolf in Hollywood. With the orphaned Peter relocated to the care of his Tommy Chong-esque grandfather in an idealized Los Angeles, Giants Are Small’s concept places the familiar story in a context both timeless and surprisingly, menacingly, wondrously modern. Composed in four days in 1936 in fulfillment of a commission for a work designed to encourage the development of musical taste among young schoolchildren, Peter and the Wolf has in the past seventy years amassed a discography containing performances narrated by luminaries of culture and politics ranging from Eleanor Roosevelt to Dame Edna Everage. Like so many works of divergent degrees of profundity, Peter and the Wolf has retained the popularity that it garnered in the decade after its first performance, according to Prokofiev a failure played to a mostly-empty house, not because it is a simplistic piece but because it cleverly, almost unperceivably inspires listeners of all ages to think and imagine. Prokofiev’s Leitmotivs in Peter and the Wolf are hardly of Wagnerian dimensions, musically or dramatically, but associating Prokofiev’s melodic units and instrumental timbres with Peter, his Grandfather, and the creatures of their acquaintance is a wonderful education in the art of interpreting musical characterization. Heightening the inherent eloquence of Prokofiev’s score, the heart of Peter and the Wolf in Hollywood beats not in a caricatured musical marionette show but in a vibrant, earnest depiction of a displaced young boy’s journey into a frightening, turbulent new world.

The brainchild of visual artist Doug Fitch, filmmaker and producer Edouard Getaz, and multimedia entrepreneur Frédéric Gumy, Giants Are Small is the product of an initiative focused on engendering fascinating new frames of reference for some of the most beloved works in the repertory. The prequel narrative devised for Peter and the Wolf, establishing Peter’s origins in Russia and the circumstances of his transplantation into the strange world of Hollywood, is nothing short of brilliant, an extension of Prokofiev’s metaphorical story that is a thoughtful, organic addendum rather than an imposition. Imaginative moments are plentiful, but the sequence at the end of the prequel linking Giants Are Small’s backstory to the adaptation of Prokofiev’s original tale proves unexpectedly moving. As Peter seeks sanctuary in his bedroom and peruses his photo album, seeing photos of himself as an infant, as a toddler, fishing by a lake, with his parents, and finally alone, the listener is given a window into the boy’s very adult senses of loss and isolation. The subsequent encounters with each member of Peter’s new milieu, including the wolf, therefore assume the increased significance of elements of the lad’s assimilation into his new existence. Aided by the voice work of Cristina Aragon as Dr. Mendoza and Fitch as the newscasters, Alice Cooper’s narration is an integral component of the tremendous success of Peter and the Wolf in Hollywood. Both in Giants Are Small’s prequel and Prokofiev’s score, Cooper’s mellifluous voice is virtually an instrument in the orchestra, used like the bassoon, the clarinet, or the oboe. Cooper’s voice is an instrument for which any composer might be proud to write. It is no surprise that Cooper’s musicality is impressive, but his affinity for Dickensian narration is unexpected. He delivers the narration without a modicum of affectation or condescension, never inflating Peter’s drama beyond the dimensions set by Prokofiev’s music. In the company of his fellow Peter narrators, Cooper’s approach combines Lorne Greene’s sonorousness, Sir Ben Kingsley’s articulation, and Sir Peter Ustinov’s sly humor but is entirely his own. It is not inconsequential when considering his musical pedigree and his faculty for revealing the music of words that Cooper’s iconic album School’s Out credited both Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim among its artistic personnel. In Prokofiev’s drama, Cooper’s performance is no less effective than his splendidly witty reading of ‘King Herod’s Song’ in the 1996 London cast recording of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar. Even in a career that has taken him to the top of the charts, this disc is one of Alice Cooper’s finest achievements.

Under the baton of young British conductor Alexander Shelley, whose rhythmic flexibility gives Prokofiev’s score an engaging ‘swing’ worthy of Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller, the young musicians of the Bundesjugendorchester play Prokofiev’s score and the excerpts from other composers’ works with an ideal combination of technical prowess and youthful exuberance. It is unfortunate that the fallacy persists that, like Humperdinck’s Händel und Gretel, Peter and the Wolf is an undemanding piece because it was conceived as an entertainment for children. Peter and the Wolf is no Siegfried or Mahler symphony, but Prokofiev’s score deserves the respect given to his ‘serious’ music. One of the foremost accomplishments of Shelley’s work to date is his uncanny gift for looking past but not indiscriminately discarding accumulated traditions and forming his own interpretations of familiar pieces. In Shelley’s hands, the music selected to complement themes from Prokofiev’s score in Giants Are Small’s prequel fits seamlessly into the flow of the story, woven together by Cooper’s vocal silk. Represented by the Prelude from Act One of Lohengrin, the Prelude from Act Three of Tristan und Isolde, and the Walkürenritt from Act Three of Die Walküre, the music of Richard Wagner is featured prominently, and the Bundesjugendorchester players maintain a high level of proficiency in the gossamer string writing. Robert Schumann’s ‘Von fremden Ländern und Menschen’ from Kinderszenen and Erik Satie’s ‘Je te veux’ make effective appearances, as do bits from the third movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, ‘Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks’ and ‘Catacombs’ from Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, the first movement of Zemlinsky’s The Little Mermaid, Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’ from Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, and the Knights’ Dance from Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet. ‘W.M.B.’ and ‘Nimrod’ from Sir Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations are thoughtfully employed, and it is intriguing to note how aptly Russian the principal theme from Bedřich Smetana’s Vltava seems in the setting of an evocation of Peter’s heritage. Only a fleeting few bars from the Largo introduction to Act Three of Puccini’s Tosca seem superfluous, but how Gershwin-like ‘Quando m’en vo,’ Musetta’s waltz from La bohème, sounds as played here! The contrasting playfulness and peril in Prokofiev’s score are intertwined spellbindingly in Shelley’s and the Bundesjugendorchester’s performance, every detail examined both for its own importance and its function in the work as a whole. Shelley’s storytelling is no less effervescent than Cooper’s, and conductor and orchestra ‘speak’ as compellingly as the narrator.

Peter and the Wolf is a work that will never gain universal acceptance among the most elitist cliques of the cognoscenti, for whom snobbery is its own kind of advocacy. It is a piece that was intended by its composer not for close study in the concert halls of great orchestras but for the enjoyment and musical edification of schoolchildren, and what is wrong with that? In a world plagued by disorder and distress, there must be moments of frivolity, moments when children and adults can come together in fun, not fear. Peter and the Wolf in Hollywood provides fifty minutes of those moments. It is a very timely reminder that, though there are dangers of which a boy can hardly dream, there are love and friendship enough in the world to sustain and swell even the smallest spark of hope.