![PERSONAL PERSPECTIVES: The Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, New York City; March 2022 [Photograph © by Joseph Newsome & Voix des Arts] PERSONAL PERSPECTIVES: The Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, New York City; March 2022 [Photograph © by Joseph Newsome & Voix des Arts]](http://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgx9qMTofnkKq6-N2Hrtf-YYT-QTS22_KLgAI9Q1NxNgV5VGKlnHy6TQesb_eCblic26klcOaceuqckz5jxn_L8wTFalLu9ktwutJKfgO2VNFCO32zw0BKpTgaHLFFbemjCQy-qJx8S53_tQy-oVdVWtHWhP-axLIICDo3Z9AB5uXYjxSYv-yRx1sQ6NaQ/s1600/Metropolitan-Opera_03-2022.jpg) House of vice or temple of Art: the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, New York City; March 2022

House of vice or temple of Art: the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, New York City; March 2022

[Photograph © by Joseph Newsome and Voix des Arts]

As has been widely reported in the press and heatedly discussed in musical circles, North Carolina-based Classical Music broadcaster WCPE, operating online as The Classical Station and on the local FM frequency 89.7, informed ‘friends and listeners’ via a letter dated 31 August and signed by General Manager Deborah Proctor of the intention to exclude six operas featured in The Metropolitan Opera’s 2023 – 2024 Season of Saturday matinée broadcasts from WCPE’s schedule owing to concerns regarding the suitability of these works for airing to the station’s audience. Citing objections to strong language and adult content, the suppression of this sextet of works is presented as a defense of morality, aimed particularly at protecting the youth among WCPE’s listeners from material deemed to be too vile for their level of maturity.

No one could contend with any degree of credibility that children in Twenty-First-Century America are not subjected to situations that exceed the limits of their still-developing comprehension. With active shooters and deadly fentanyl invading their schools, how could American children fully understand the perils to which their society exposes them? However, one aspect of humanity that should never be underestimated is a child’s capacity to learn from and adapt to even the most difficult circumstances and surroundings. Those parties who justify their actions with allusions to Scripture should be reminded that Deuteronomy 4:9 records that Moses instructed that an adherent to a righteous path should ‘keep thy soul diligently, lest thou forget the things which thine eyes have seen, and lest they depart from thy heart all the days of thy life: but teach them thy sons, and thy sons' sons.’ Children learn by experiencing and communicating, not by being sheltered and lectured. Rather than safeguarding innocence, silencing artistic expression in any form teaches children to reject what they do not know or understand.

WCPE’s business model, whereby the station’s operations are funded wholly by financial contributions from listeners and community supporters, necessitates involving or at least considering the interests of those benefactors in deliberations about programming. Still, managing an entity like WCPE entails a responsibility to serve—the distinction of service here being extraordinarily important—as a conduit for conversation. Imposing one’s own biases and/or those of a group of listeners upon the total population is contrary to the most basic tenets of artistic leadership. With dedication to service to community comes a critical responsibility to represent that community in decisions and deeds. Willfully endeavoring to sanitize the creative products of some sectors of the community asserts that others within the community lack the intelligence and intuition to make their own choices.

There is a fundamental difference between a supporter-funded, free-access broadcaster and a subscription-based service. The exasperating prevalence of the same names and same pieces in WCPE’s listener-request programs on Fridays and Saturday evenings suggests that the station permits some contributing listeners to use the station as a personal playlist. Problematic though this is, it is not an unreasonable display of gratitude when confined to those specific broadcast slots. When allowed to affect a cornerstone of WCPE’s programming like the MET’s Saturday matinée broadcasts, this subjugation of universal free will to personal opinion betrays the trust of all listeners, whether or not they are contributors to the station.

The inclusion of the operas targeted by WCPE—and, make no mistake, the station’s action is tantamount to a focused assault on freedom of expression as egregious and reprehensible as the censorship that occurs with regularity in cultures considered inimical to American ideals—in the MET’s Season has spurred discourse on which musical styles and dramatic elements should be granted places in the MET repertory. Such discourse is invaluable, but depriving listeners of opportunities to hear and assess controversial works yields uninformed disputes and wholesale dismissals that damage and ultimately destroy Art and undermine the unity that Art fosters. Each listener exercises the authority to embrace or renounce these operas. By seeking to usurp that authority, WCPE’s General Manager demonstrates appallingly poor judgment, signaling to the station’s listeners that their competence ends at tuning in to WCPE.

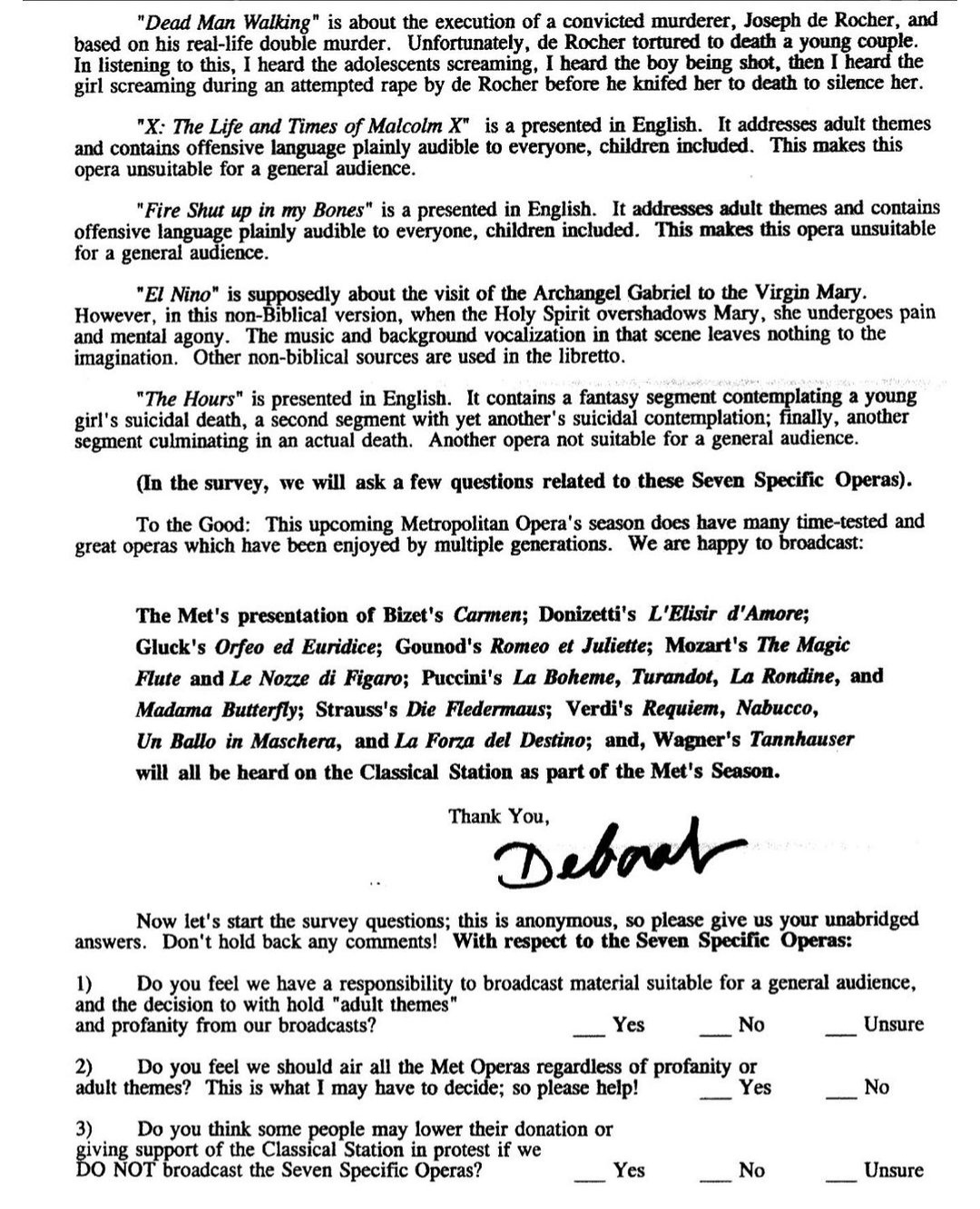

Page (1) of WCPE’s 31 August letter to ‘friends and listeners’

Page (1) of WCPE’s 31 August letter to ‘friends and listeners’

[click on image to enlarge]

Page (2) of WCPE’s 31 August letter to ‘friends and listeners’

Page (2) of WCPE’s 31 August letter to ‘friends and listeners’

[click on image to enlarge]

Among the many absurdities included in WCPE’s communication to ‘friends and listeners,’ none is more indefensible than the argument that Mexican composer Daniel Catán’s 1996 opera Florencia en el Amazonas—a title that the letter’s author mangled whilst purporting to have become acquainted with the piece for the purpose of rejecting it—violates the station’s undefined ‘musical format guidelines.’ Is Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme in Moses und Aron more palatable? Did the innovative sounds heard in Tan Dun’s The First Emperor, Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice, and Brett Dean’s Hamlet—operas aired by WCPE—conform to the station’s standards?

The violent rape and murder central to the storyline of Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking are undeniably abhorrent, but is the opening scene of Mozart’s Don Giovanni less revolting for being set to music of typical Eighteenth-Century refinement? Mozart’s unrepentant Giovanni is dragged to hell in the opera’s penultimate scene. De Rocher, the monstrous killer in Dead Man Walking, is executed for his crimes. The WCPE letter complains of the screams of a young girl enduring sexual assault being heard in Dead Man Walking. What, then, are the repeated top As in Donna Anna’s ‘Or sai chi l’onore,’ in which she recounts her own trauma, and the top B with which Puccini’s Turandot relives her ancestor Lou-Ling’s ‘quel grido e quella morte’?

John Adams’s El Niño is condemned because its libretto makes use of ‘non-biblical sources.’ Should Bellini’s I Capuleti ed i Montecchi be similarly denied airtime because its libretto is not derived from Shakespeare? Should the many Nineteenth-Century scores with plots taken from the writings of Schiller be shelved in protest of their librettists’ neglect of ‘correct’ original source material?

It is stated that objection to the subject matter in Kevin Puts’s The Hours relates to the opera’s depictions of contemplations and acts of suicide, yet Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and Turandot, in which Cio-Cio San and Liù respectively end their own lives, are deemed to adhere to the station’s standards of decency. Is it better, then, to slaughter oneself in Italian than to perish in English?

At issue in Anthony Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X and Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones is vulgar language which the composers and their linguistic collaborators failed to render tolerable to WCPE by translating it into French, German, or Italian. What might WCPE management have thought of some of Beverly Sills’s colorful interjections into Marie’s dialogue in her English-language performances of La fille du régiment? Natalie Dessay was not banned from the station for exclaiming ‘Merde!’ in the broadcast of the MET’s Laurent Pelly production of Fille, but she had the good manners to swear en français.

With a grammatical misstep, the author of WCPE’s haphazardly-written letter unintentionally got one thing right: indeed, ‘not airing modern, discordant, and difficult music is [a] concern.’ It is true that the majority of people who purchase tickets for Rolling Stones concerts do so with the expectation of hearing ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash,’ ‘Ruby Tuesday,’ and ‘Satisfaction,’ but few of them boo when new material is performed alongside the classic hits. WCPE’s weekly, one-hour Wavelengths program—dropped by the station earlier in 2023—featured contemporary music, but advancing this as genuine open-mindedness and advocacy for new works was akin to an opera company occasionally staging Porgy and Bess as evidence of its diversity rather than regularly auditioning and engaging artists of color. WCPE’s stated emphasis on Baroque, Classical, and Early Romantic works could perhaps be respected as a valid reflection of listeners’ preferences were it not so obviously belied by frequent airings of music by Mahler and Debussy and excerpts from film scores.

What is all too apparent in WCPE’s letter is a regrettable prejudice against contemporary modes of operatic expression, particularly those that tell the stories of marginalized peoples who have been traditionally victimized or ignored by the Arts. Art is inherently political, but the enjoyment and celebration of Art and the artists who create it should never be politicized in the pursuit of a personal agenda. Should those who are disturbed by the graphic violence in Dead Man Walking, which is no more distressing than reporting on the evening news, also be denied the chance to contemplate the redemption engendered by the ‘face of love’ and forgiveness? WCPE’s action is censorship not of offensive material but of glimpses of situations too honest and human to be depicted with pretty tunes.

Had Abraham Lincoln—an opera lover who wrote of a special fondness for Gounod’s Faust—been the director of an opera company, he might have said that one can please some operaphiles some of the time and all of them some of the time but never all of them all of the time. Would he have liked the operas composed since his assassination? That cannot be known, but it is unlikely that he would have supported the repression of music that he did not like. Surely it is better to honor the right of all work to be heard, ‘with malice toward none, with charity for all.’