Image may be NSFW.

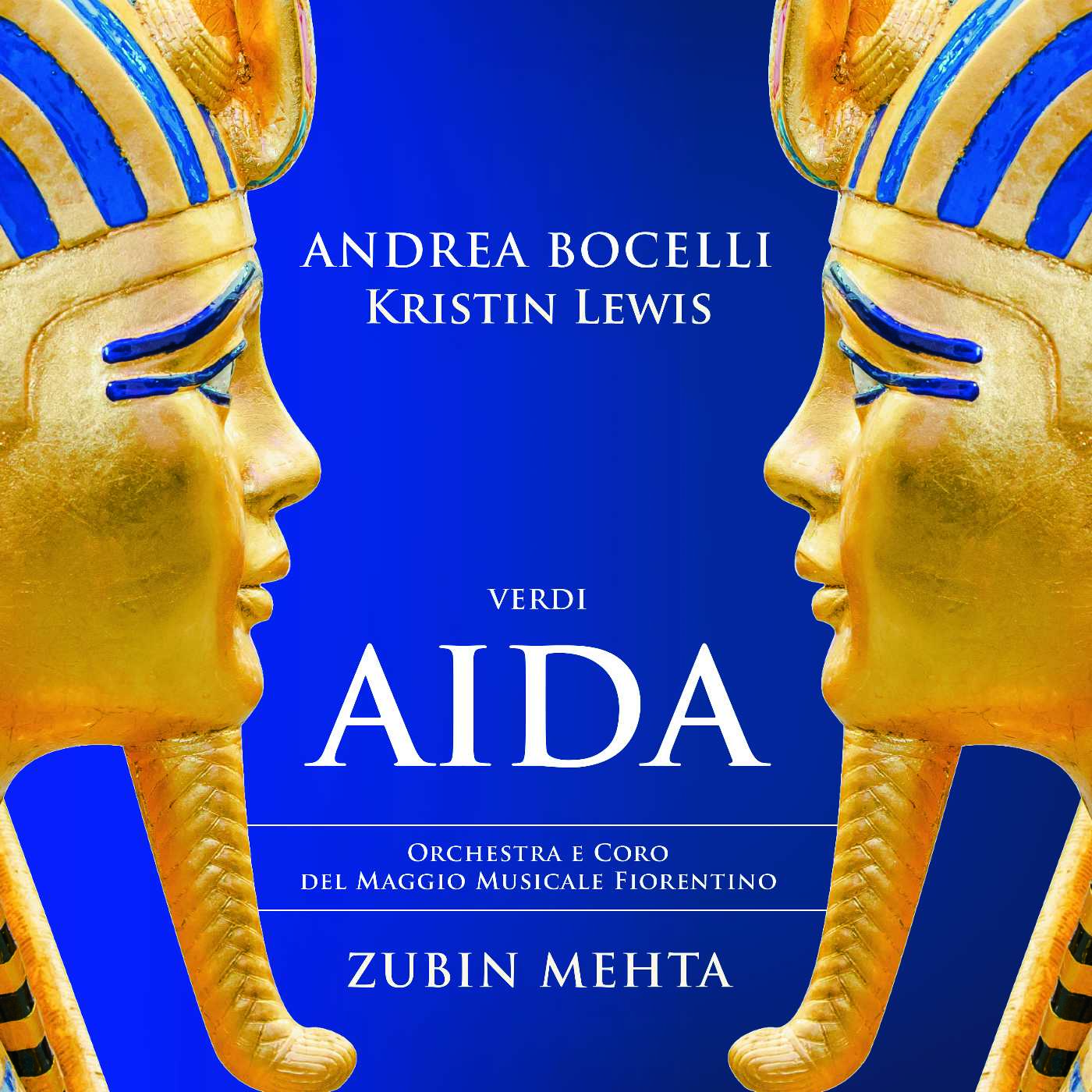

Clik here to view. GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Aida—Kristin Lewis (Aida), Andrea Bocelli (Radamès), Veronica Simeoni (Amneris), Ambrogio Maestri (Amonasro), Carlo Colombara (Ramfis), Giorgio Giuseppini (Il re d’Egitto), Maria Katzarava (Una sacerdotessa), Juan José de León (Un messaggero); Coro ed Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino; Zubin Mehta, conductor [Recorded at the Opera di Firenze, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Florence, Italy, 11 – 15 April 2015; DECCA 483 0075; 2 CDs, 145:54 Available from Amazon (USA), iTunes, fnac (France), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Aida—Kristin Lewis (Aida), Andrea Bocelli (Radamès), Veronica Simeoni (Amneris), Ambrogio Maestri (Amonasro), Carlo Colombara (Ramfis), Giorgio Giuseppini (Il re d’Egitto), Maria Katzarava (Una sacerdotessa), Juan José de León (Un messaggero); Coro ed Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino; Zubin Mehta, conductor [Recorded at the Opera di Firenze, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Florence, Italy, 11 – 15 April 2015; DECCA 483 0075; 2 CDs, 145:54 Available from Amazon (USA), iTunes, fnac (France), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

When delays spawned by the ill-timed start of the Franco-Prussian War were circumvented and Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida finally received its première at Cairo’s Khedivial Opera House on 24 December 1871, it was apparent that Italy had at last produced a grand opera to challenge the epic-scaled French scores of Giacomo Meyerbeer and Fromenthal Halévy. Combining extraordinarily demanding rôles for each of the common Fächer and tremendous choral tableaux with episodic dances and grandiose scenic effects, Aida gave the Italian repertory a wholly worthy companion to Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots and Robert le diable and Halévy’s La Juive. Aida is indisputably grand opera at its grandest, but it is also representative of Verdi at his most Verdian: amidst the opera’s spectacular tumult, emerging from the reeds along the banks of the Nile and the spoils of conquest there is the acute intimacy of human relationships. Though Aida is, like Les Huguenots, populated by exalted personages, the interactions among Aida, Amneris, Radamès, and Amonasro are the tribulations of ordinary people in extremis, not merely political collisions among states. Not even the greatest artist can fully transform Meyerbeer’s Marguerite de Valois from an archetype into a woman like any other, but the soprano who heeds the dictates of Verdi’s score can hardly fail to sense and project the humanity that makes Aida one of opera’s most persuasive protagonists. There is no question that this new DECCA Aida owes its existence to its Radamès, but the recording, benefiting from Maggio Musicale Fiorentino’s decades-long familiarity with the music of Verdi, offers a genuine ensemble in the principal rôles, making this an Aida not of impersonal exclamations but of earnest conversations. Especially with today’s paucity of Verdi voices, a perfect Aida is as elusive as an ideal Così fan tutte or Parsifal, but even this Aida’s imperfections often make valid points about the music and the characters who sing it.

As suggested, the playing and singing of the Coro ed Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino are the solid foundations upon which this Aida rises. The choristers’ singing is unfailingly energetic, too much so in a few passages of ragged ensemble, and mostly effective regardless of occasionally sounding artificially recessed. Problems of balance often intrude into the sonic landscapes of this recording, with singers often sounding as though they were recorded in separate acoustics. In the trio for Aida, Amneris, and Radamès in Act One, for instance, each voice seems to occupy a different sonic space, lessening the impact of this first confrontation between the two women whose actions instigate the opera’s tragedy. Still, the choral singers acquit themselves admirably, and their work is supplemented by the orchestra’s vibrant playing. Here, too, there are sporadic misadventures, accentuated by the recorded ambiance. In particular, there are strange sounds from the percussion, one of the most perplexing of which is an unnecessarily cacophonous clang at the end of the Act Four scene for Amneris and Radamès. The oboe and clarinet phrases in ‘O patria mia’ are lovingly rendered, and the wind playing is exemplary throughout the performance. The strings are thoroughly professional without being uniformly exceptional, their parts executed with easy proficiency that does not preclude a few instances of thinness on high, likely exacerbated by the recording. The choristers’ and instrumentalists’ efforts are marginally undermined, but the advantages of their acquaintance with Verdi’s music is never impeded.

Mumbai-born maestro Zubin Mehta’s history with Verdi’s Aida is as extensive as any relationship between conductor and score in opera today. It was on the podium for a 1965 performance of Aida featuring Gabriella Tucci, Franco Corelli, Rita Gorr, and Anselmo Colzani that Mehta débuted at the Metropolitan Opera, and his MET Aidas in the seven subsequent performances in the 1965 – 1966 Season over which he presided were Martina Arroyo and Leontyne Price. Mehta’s first studio recording of Aida, a product of the mid-1960s, had among its cast Birgit Nilsson as Aida and Corelli as Radamès. Perhaps the presence of these vocal titans accounts for some of the marked differences between that Aida and this DECCA recording. The bristling dramatic thrust of the earlier recording, lifting the performance out of the studio despite singing from Nilsson that is never entirely idiomatic, is notably missing from this new recording. Mehta’s tempi are not exclusively slow, but many pages of the score here sound lethargic. Whether a conductor has at his disposal singers like Giulietta Simionato and Mario del Monaco or more earthbound vocalists, when a scene like that for Amneris and Radamès in Act Four—one of the most thrilling, tautly-constructed scenes in opera—fails to take flight something is wrong. Mehta’s instincts in general and in this performance are too musical to permit absolute failure, but there are enough shortcomings here to question the preparation that preceded the making of this recording. Comparing this Aida to Mehta’s HMV studio recording and broadcasts of other performances of the opera that he has conducted, it is difficult to believe that, as is stated in the liner notes, all of the musical forces were assembled in Florence under the conductor’s supervision for five days in April 2015. With a conductor of Mehta’s proven faculties in Verdi repertory at the helm, how can such a lifeless Aida have issued from circumstances conducive—if they were as they are asserted to have been—to fast-paced musical momentum?

Aside from its American Aida, only the Messaggero and Sacerdotessa in this Aida are not native-born Italians, yet theirs is some of the best singing heard on these discs. Texas native tenor Juan José de León brings bright, focused tone to the Messaggero’s fateful news of the Ethiopians’ advance towards Egyptian territory. Bel canto repertory is his usual habitat, but the verbal acuity that serves him so well in Donizetti rôles is no less valuable in Verdi’s music. Mexican-born soprano Maria Katzarava, the unforgettable Leonore in Opera Carolina’s 2015 production of Beethoven’s Fidelio [reviewed here], voices the Sacerdotessa’s exotically melodic ‘Possente, possente Fthà’ marvelously, the garnet timbre of her voice and her unaffected diction striking precisely the right chord of reverent mystery. Her muted repetition of ‘Immenso, immenso Fthà’ in the opera’s final scene is equally ethereal. How many singers who have recorded the priestess’s music can assuredly be said to equal Katzarava as a Sacerdotessa eminently qualified to sing Aida?

So prevalent has dry, wobbly singing of Aida’s bass rôles become that it might be supposed that Verdi’s score explicitly requests desiccated, unsteady vocalism. This Aida reaps the rewards of the participation of two basses who defy the trend by singing strongly and solidly. It was during an ill-fated 2010 performance of Don Carlos that Giorgio Giuseppini débuted at the Metropolitan Opera as another of Verdi’s troubled kings, Filippo II, substituting for an indisposed Ferruccio Furlanetto. A well-travelled Ramfis, Giuseppini sings il re d’Egitto in this performance, making his best stab at igniting a dramatic conflagration with a flinty account of ‘Su! del Nilo al sacro lido.’ Giuseppini’s vocalism is not opulent like Italo Tajo’s and Plinio Clabassi’s, but it is fantastic to encounter a Pharaoh who does not sound as old and weather-worn as the pyramids at Giza. Carlo Colombara is a veteran Ramfis whose experience lends his portrayal of the implacable character a slashing histrionic edge. Beginning with his firm articulation of ‘Sì: corre voce che l’Etiope ardisca’ in the opera’s first scene, Colombara establishes Ramfis’s significance in the drama. He declaims ‘Gloria ai Numi! Ognun rammenti ch’essi reggono gli eventi’ with authority, and his singing of ‘Ascolta, o Re: tu pure, giovine eroe, saggio consiglio, ascolta’ exudes ruthlessness. In both the scene with Amneris at the start of Act Three and the Judgment Scene in Act Four, Colombara’s Ramfis is a towering presence, a man who delights in his ability to subjugate even the mightiest in his society with his dispensation of unanswerable moral superiority. Colombara’s performance is not subtle, but neither is the character he depicts. Like Giuseppini, he impresses as much with what his singing lacks as with what it possesses.

Aida’s father Amonasro is one of the most difficult of Verdi’s baritone rôles. Lacking the opportunities for character development through vocal display that Verdi granted most of his baritone leads, an Amonasro must toil diligently within the relatively brief span of his part to expose the psychological depth with which the composer and his librettist, Antonio Ghislanzoni, infused the captive Ethiopian king. Much is revealed about Amonasro by his first utterance in the opera, ‘Non mi tradir!’: reunited with his daughter after a separation of unknown duration, his first words to her are not a tender paternal greeting but an exhortation to maintain the secrecy of his true rank. In this Aida, baritone Ambrogio Maestri is a scrupulously musical Amonasro who works hard to eschew the unseemly barking and bellowing that are too often substituted for singing the part. Best known outside of his native Italy for comic rôles, Maestri also has extensive credentials in dramatic parts. In this performance, he follows an impactful statement of his opening ‘Non mi tradir!’ with a reading of ‘Suo padre... Anch’io pugnai... Vinti noi fummo e morte invan cercai’ that radiates thwarted sovereignty. In the pivotal Act Three scene with his daughter, a gentler facet of Maestri’s Amonasro is manifested in his voicing of ‘A te grave cagione mi adduce, Aida,’ but the stony-hearted monarch returns in ‘Non fia che tardi — in armi ora si desta il popol nostro — tutto pronto è già.’ Verdi’s directive con impeto selvaggio in the passage beginning with ‘Su, dunque! sorgete Egizie coorti, col fuoco struggete le nostre città’ is meticulously observed, and the vengeful glee of Amonasro’s interjection of ‘Di Nápata le gole! Ivi saranno i miei...’ after Aida cajoles the unwitting Radamès into betraying the Egyptians’ battle plan explodes from the baritone’s throat. Maestri consistently sings well, his command of the music’s tessitura exposing no deficiencies in the voice’s support. The baritone’s Amonasro ultimately is not as imposing as Warren’s, as frightening as Gobbi’s, or as inherently noble as Taddei’s, but his performance is assertive, bold, and legitimately Italianate. Most importantly, Maestri is the rare Amonasro who sings as well as he snarls—better, in fact.

If Amonasro’s music frequently induces muscular shouting, Verdi’s music for the Egyptian warrior Radamès no less frequently receives from tenors one-dimensional wailing and whining. Though he studied with Corelli, one of the Twentieth Century’s most celebrated exponents of Radamès, the rôle is not a natural fit for Andrea Bocelli’s lyric instrument, but many tenors with vocal endowments more modest than the part’s spinto requirements have successfully sung Radamès. From the start of his stentorian recitative ‘Se quel guerriero io fossi! se il mio sogno si avverasse!’ in Act One, Bocelli’s crystalline Italian diction is splendid, and he is punctilious in refraining from forcing his voice in the famous aria ‘Celeste Aida.’ Following Corelli’s lead, he executes the arduous diminuendo on the aria’s climactic top B♭, likely profiting from discreet electronic assistance. In the aria and the scene with Amneris and Aida that follows, his voice rings out heroically, the close recording of periodically highlighting slight breathiness. In the grand public scenes in Acts One and Two, Bocelli sings Radamès’s lines in ensembles robustly. In his entrance in the passionate duet with Aida in Act Three, the tenor voices ‘Pur ti riveggo, mia dolce Aida’ with roiling ardor, and he phrases ‘Sovra una terra estrania teco fuggir dovrei!’ amorously. Like most tenors, Bocelli clearly relishes the exposed top As on ‘Sacerdote, io resto a te’ at the act’s end, hurling the notes out with abandon. In the incredible scene with Amneris in Act Four, Bocelli sings ‘Di mie discolpe i giudici mai non udran l’accento’ perceptively, his Radamès’s defiance of the arrogant princess stinging but not devoid of compassion. Facing his condemnation with resolve, this Radamès articulates ‘La fatal pietra sovra me si chiuse... Ecco la tomba mia’ with a stirring blend of courage and sorrow. His agitation as he realizes that Aida has concealed herself in the tomb with him is indicative of the enormity of his affection for her, and Bocelli and his Aida sing ‘O terra, addio; addio valle di pianti’ not as an elegy but as a paean to their liberating love. That Bocelli is a Radamès who would be overwhelmed by attempting to project the music into the vast spaces of the Arena di Verona, the Metropolitan Opera, or Teatro alla Scala is undeniable, but the seating capacity of the Khedivial Opera House in which Aida was first performed was approximately 850. In that setting, singing as he sings on this recording, he might have been unexpectedly convincing. There are moments of vocal discomfort in this performance, but Bocelli’s painstaking commitments to both music and text are irreproachable.

Like Azucena in Il trovatore, Amneris is a rôle that demands almost superhuman reserves of vocal and dramatic stamina. Like Amonasro, she has no showpiece aria in which to refine her persona, but her music is the kaleidoscopic raw material from which the picturesque mosaic of Aida is assembled. Assuming her place in the lineage of Bruna Castagna, Ebe Stignani, Giulietta Simionato, Fedora Barbieri, and Fiorenza Cossotto, Roman mezzo-soprano Veronica Simeoni here depicts an emotional but curiously subdued Amneris whose edge of ferocity is blunted by the singer’s cautious avoidance of chest register. The cumulative potency of Simeoni’s singing in the Act One scene with Radamès and Aida, launched promisingly with an aptly haughty reading of ‘Quale insolita fiamma nel tuo sguardo,’ is compromised by an account of ‘Trema, o rea schiava, ah! trema ch’io nel tuo cor discenda!’ with a disfiguring dearth of venom. Like Bocelli, the mezzo-soprano performs her lines in the large ensembles with finely-judged tone and excellent diction. In the puzzling scene with her slaves at the beginning of Act Two, Simeoni is the rare Amneris who makes something provocatively sensual of the sinuous statements of ‘Vieni, amor mio, mi inebria... Fammi beato il cor!’ Joined by her rival for Radamès’s love, this Amneris’s furious irony in ‘Fu la sorte dell’armi a’ tuoi funesta, povera Aida!’ is surprisingly innocuous, the singer’s tones just uneven enough to impair her histrionic intentions. Finding Radamès inadvertently colluding with Amonasro in Act Three, Simeoni’s cry of ‘Traditor!’ conveys the princess’s shock and despair. As she ponders at the start of Act Four how to rescue Radamès from the wrath of Ramfis and his coven of priests, this Amneris caresses the melodic line of ‘L’aborrita rivale a me sfuggia’ as though she is aware on some level that this is as near as she will come to holding the remorseful but unapologetic object of her desire in her arms. Endeavoring one last time to bend him to her will in ‘Già i Sacerdoti adunansi arbitri del tuo fato,’ Simeoni’s Amneris is vanquished by Radamès’ determination to unfalteringly face his sentence but not before detonating a pair of spot-on top B♭s. In the formidable Scena del Giudizio, Simeoni sings ‘Numi, pietà del mio straziato core’ athletically, and she ends the scene with a sonorous top A. The firepower of the music that came before notwithstanding, this Amneris is most moving in the hushed, guilt-ridden pleas for absolution in the opera’s final scene. Simeoni here clearly understands and reacts to Amneris’s emotions, and her singing pulses with sincerity. Simeoni’s voice has great potential, but in the performance on these discs she is not yet a fully-developed Amneris in the tradition of her Italian forebears. As her stage experience in the rôle grows, Amneris will likely come to more completely inhabit her voice and her heart.

Documenting a portrayal with which she has conquered many of Europe’s most prestigious stages, including those of the Wiener Staatsoper, Milan’s Teatro alla Scala and the Arena di Verona, where staging Verdi’s Egyptian epic is as much a sport as an art, Arkansas-born, Vienna-based soprano Kristin Lewis is a conflicted, often beautifully-sung Aida who comes frustratingly close to unmitigated success in this mercilessly demanding rôle. The DECCA catalogue documents the Aidas of Renata Tebaldi, Leontyne Price, and the idiosyncratic but plausible Maria Chiara, in addition to excerpts featuring the Aida of Birgit Nilsson. Visually, Lewis is the equal of the most glamorous, fetchingly beautiful Aidas in the opera’s history, but in the context of this recording she is not yet a totally satisfying Aida. When first heard in Act One, her ‘Ohimè! di guerra fremere l’atroce grido io sento’ sounds as though the voice emanates from a different, less-flattering acoustic than that in which her colleagues’ voices are centered. Having weathered the indignities of the Egyptians’ raucous readying for battle, Lewis’s Aida begins ‘Ritorna vincitor!… E dal mio labbro uscì l’empia parola!’ with the bitter taste of her countrymen’s blood flooding her senses, barely capable of repeating the hated words calling for her enemies’ victory. With her entreaty of ‘Numi, pietà — del mio soffrir,’ the soprano’s vocal demeanor softens markedly, and the text pours out on a stream of golden tone. Throughout the performance, Lewis’s singing is most attractive when the voice is not under pressure, but Aida is not a rôle in which carefree moments prevail.

An illustrative example of what Lewis brings to the part is Aida’s Act Two scene with Amneris. Meeting her adversary in a duel of wits, Aida struggles to retain her grasp on whatever upper hand decorum affords her. Mindful of this, Lewis delivers ‘Ah! pietà!... che più mi resta? Un deserto è la mia vita’ with touching simplicity, saving her cunning for answering Amneris’s insinuations and veiled threats. Later, she handles the crests of the Scena trionfale with aplomb. Aida faces her greatest tests in Act Three, in which Verdi asks her to negotiate the very different vocal obstacles of a demanding aria—the aria by her performance of which many listeners unfairly assess an Aida—and duets with Amonasro and Radamès. Lewis uses the text of the recitative ‘Qui Radamès verrà... Che vorrà dirmi?’ as a springboard via which she rockets into ‘O patria mia.’ Her heartfelt, mezza voce performance of the aria, capped with a secure, superbly-sustained top C, grants the number the introspective core Verdi surely intended it to have. Aida’s amazement at her father’s intrusion into her reveries is meaningfully expressed, and Lewis then returns every volley lobbed at her by Maestri in the scene with Amonasro, furnishing some ecstatic top notes. The soprano’s efforts at spotlighting the contrasts between ‘Un giorno solo di si dolce incanto... Un’ora di tal gaudio... e poi morir!’ and ‘Padre, a costoro schiava io non sono’ yield spellbinding results. Deceiving Radamès at her father’s bidding, Lewis’s Aida is appalled by her own duplicity as she sings ‘Fuggiam gli ardori inospiti di queste lande ignude’ to her paramour. The terror of their discovery by Amneris and Ramfis shudders through the soprano’s enunciation of ‘La mia rivale!’ at the act’s end.

Relieved of the necessity of battling for survival, Aida embraces the inner peace that has eluded her throughout the opera by pledging to meet death at Radamès’s side in the subterranean crypt to which Ramfis’s dogged justice dooms him. The sound of Lewis’s voicing of ‘Presago il core della tua condanna’ is that of a spirit on the precipice between life and death, the tortures of the former dissolving into the blessed oblivion of the latter. The delicacy of Lewis’s phrasing in ‘O terra, addio; addio valle di pianti’ offsets Bocelli’s tendency to blare above the stave, her sparkling top B♭s soaring above the gossamer orchestral textures. Like Wagner’s Senta and Isolde, this Aida seems more transfigured than overcome by death: it is a transition rather than a termination. Still barely past thirty, Lewis is a very young Aida, a relative novice—albeit already a practiced one—in a rôle in which many sopranos of prior generations did not reach their primes until at least a decade later. When Leontyne Price bade the Metropolitan Opera adieu with a performance of Aida in January 1985, five weeks before her fifty-eighth birthday, she remained capable of portraying Aida dazzlingly, musically and dramatically. With such an iron grasp on the part at this juncture in her career, Lewis has the skills necessary to blossom from this auspicious performance into the sort of Aida for which opera lovers long.

After declining the financially-lucrative offer to conduct the Cairo première of Aida, Verdi wrote to a friend, ‘It seems to me that art looked at in this way is no longer art, but a trade, a party of pleasure, a hunt, anything that can be run after, to which it is desired to give, if not success, at least notoriety at any price.’1 How prescient he was! Much as opera as a commodity seems an invention of the last half-century, Verdi was conscious more than a century ago of the hazards that hype posed to opera. There are those among today’s opera aficionados who will dismiss this DECCA Aida as a business venture rather than an artistic endeavor because of one member of its cast. It is regrettable that, almost 145 years after Aida was first performed, Verdi’s wisdom will likely be reaffirmed by closed minds unwilling to acknowledge that even very popular ‘crossover artists’ are capable of enjoyable, thoughtfully-conceived ‘serious’ singing. Perhaps the target market for this Aida is not the ranks of connoisseurs who cling to their decades-old Aidas, but the listener who truly loves Verdi will find among definite weaknesses in this recording many virtues that expunge any suspicions of pursuit of ‘notoriety at any price.’

_____________________________________________________________________

1 Giuseppe Verdi to Milan-based critic Filippo Filippi (1830 – 1887), 9 December 1871